WHEN challenged by Jeremy Corbyn to explain stagnating wages, Theresa May demurred, instead reassuring underpaid employees that “the strong and stable leadership of the Conservatives” would revive the economy. When questioned by Andrew Marr, a television host, about raising taxes, Mrs May gave no fiscal plans, but hoped to reduce the burden through “strong and stable leadership”. Even when asked on BBC Radio Derby to define a “mugwump”—a 19th-century insult which Boris Johnson, the foreign secretary, had directed at Mr Corbyn—she replied: “What I recognise is that what we need in this country is strong and stable leadership”.

Mrs May’s repetition of the phrase has become, to use Mr Marr’s description, robotic. After imploring her to cut it out at the start of his 20-minute interview on April 30th, she managed to squeeze it in four times, with 16 mentions of strength—about one every eight sentences. The parroting seems so cynical that voters must eventually tire of it. Recent history suggests otherwise. The tactic has scored some spectacular victories, and has its roots in research about how the brain responds to campaign messages.

Slogans, of course, are as old as elections themselves: they are scribbled on the walls of Pompeii, while American politicians have worked with advertisers since the 1920s, says Steven Barnett, a professor of communications at the University of Westminster. Tony Blair might seem the prototype of the modern soundbite-spewer, with his promises to focus on “education, education, education” and to be “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime”. But in two hours of primetime campaigning in the 1997 election—in interviews on “Panorama” , “Newsnight”, and “Question Time”—he used neither of those catchphrases, and only mentioned “New Labour” when explicitly asked about it.

Where once these expressions made for headlines and occasional references in stump speeches, they are now the very fabric of English political language. Much of the blame rests with Sir Lynton Crosby, one of a team of strategists advising Mrs May. After coaching Australia’s Liberal Party to four consecutive electoral victories, Sir Lynton belatedly took over the Conservative Party’s doomed general-election campaign in 2005. He subsequently guided Mr Johnson to back-to-back mayoral wins, and in 2015 got a second chance at a general election. The hard-nosed Aussie had hitherto been known for his “dog-whistle” slogans: “How would you feel if a bloke on early release attacked your daughter?” ran one from 2005.

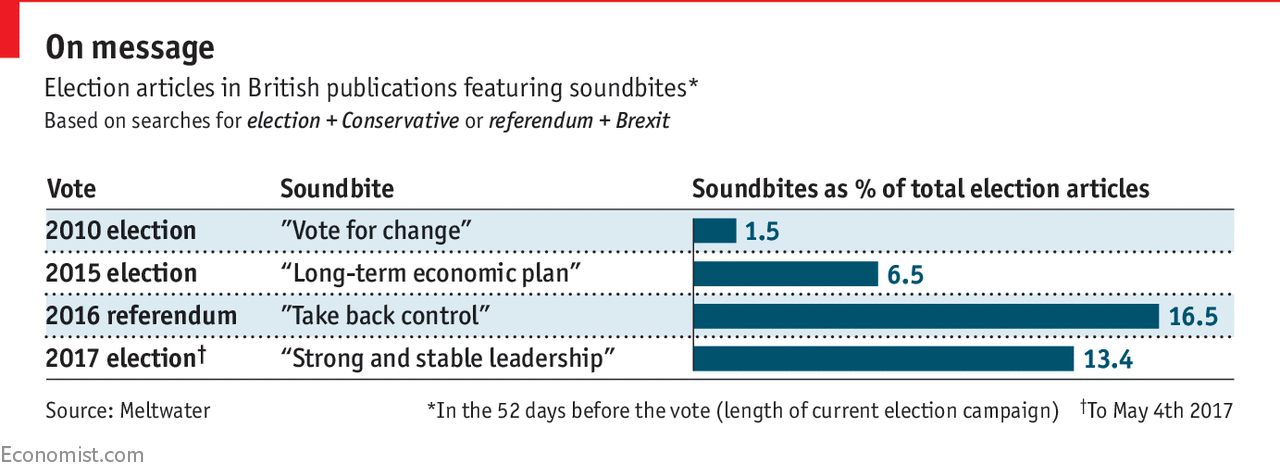

Ahead of the 2015 election, Sir Lynton apparently realised that a lack of a clear message cost the Conservatives a majority in 2010. He had a point. You have probably forgotten the official motto, “vote for change”. According to Meltwater, a media monitoring tool, the phrase appeared in just 581 articles by British publications in the 52 days before the election (the length of the current campaign). That is 1.5% the number of pieces that featured the words “election” and “Conservative”. There were 454 mentions of “I agree with Nick”: David Cameron’s televised concession to Nick Clegg, the leader of the Liberal Democrats, with whom he would end up in coalition.

In the decade between his two elections Sir Lynton picked up some new tricks. In a lecture from 2013 about his campaign philosophy, he explained that “message matters most”; the millions spent on advertising and direct mail are worthless without a compelling line.

But he also revealed that he had read and admired “The Political Brain”, a book published by American psychologist Drew Westen in 2007, and quoted from it: “in politics, when reason and emotion collide, emotion invariably wins”. Mr Westen, a professor at Emory University, had scanned the brains of Democratic and Republican supporters while showing them a series of conflicting statements by the leader of their party and then asking for their reactions. When the statements contradicted each other (such as a reversed campaign promise), the neural circuits for negative emotion switched on—before flickering off as positive emotions kicked in. Nothing much happened to the circuits involved in reasoning. All this occurred before subjects were asked about the conflict, which they mostly denied perceiving. In other words, voters had suppressed negative political feelings without much need for thought.

Mr Westen’s observations convinced him that “the political brain is an emotional brain. It is not a dispassionate calculating machine, objectively searching for the right facts, figures and policies to make a reasoned decision.” Feelings predated thoughts in our evolutionary development, and occupy more cerebral space. The art of persuasion, he wrote, “is creating, solidifying and activating networks that create primarily positive feelings toward your candidate or party”. Emotion, not argument, wins the day. For strategists:

The goal is to convince voters that your candidate is trustworthy, empathic, and capable of strong leadership, and to raise doubts about the opposition along one or more of these dimensions.

Barack Obama’s run for the American presidency in 2008 was a fine example: “yes we can” ran the slogan. A “long-term economic plan”, the Conservative catchphrase in 2015, seems comparatively dry. Yet it was still a product of Mr Westen’s advice. Referring once again to “The Political Brain”, Sir Lynton told the Oxford Union in 2016 that “the emotional element was the risk to those jobs, the risk to that economic plan that Ed Miliband and his weakness would pose”. The slogan was a simple statement about trustworthiness, not a raft of fiddly policies. It popped up in 6.5% of pre-election articles (see chart). Appearing on Mr Marr’s show, George Osborne, the chancellor, referred to a “sensible” or “balanced” plan 15 times. Labour’s eight-foot stone tablet of campaign promises, by contrast, allowed the medium to become the message.

In 2016 the soundbite came into its own. Matthew Elliott, the chief executive of the Vote Leave crusade in the Brexit referendum, says his experience in the Alternative Vote referendum of 2011 suggested that emotive messaging could beat arcane arguments. Mr Elliott’s NOtoAV team stressed the cost of ditching first-past-the-post: posters claimed the putative £250m bill would be better spent on bulletproof vests for soldiers or maternity units. His side won by 35 points, having trailed in early polls. That strategy returned in the Brexit campaign, most obviously in the (somewhat dubious) pledge to spend the weekly £350m contribution to the European Union on healthcare, but also in the rallying cry to “take back control” of borders and sovereignty. Both slogans were tested in weekly focus groups and ingested by supportive politicians. “Take back control” appeared in 16.5% of articles about Brexit. The notoriously unscripted Mr Johnson used it five times in his pre-referendum chat with Mr Marr, with 13 mentions of control in all. Perhaps the most emotive quip belonged to Michael Gove: “enough of experts” is not much of an appeal to reason.

And then there was Donald Trump—hardly “on message”, and certainly not attentive to brain scans. His skills as a salesman, however, produced a number of rousing lines: “make America great again” fits Mr Westen’s recommendations exactly. What chance had “I’m with her”, Hillary Clinton’s line, against “build the wall”, “drain the swamp” and “lock her up”? Nobody will be chanting “strong and stable leadership”, “deep and special relationship” or “coalition of chaos” at a rally. But the intended effect is the same.

Sir Lynton argues that such messages “cut through the static” of 24-hour television and social media. Opposition parties should take note. Just 2% of voters can recall Labour’s motto, “for the many, not the few”, compared with 15% for “strong and stable leadership”. Mr Corbyn’s Twitter feed is filled with policies about the NHS, housing and policing. Mrs May’s? You guessed it

Photo by Thomas Charters on Unsplash