Playboy magazine’s announcement that it will be bringing naked pictorials back to its pages after a year’s absence was strangely timed to coincide with Valentine’s Day. But it was not a declaration that pulled at my heartstrings.

Cooper Hefner, the 25-year-old son of Playboy founder Hugh, and now the magazine’s chief creative officer, said removing nude images had been a mistake. Under the hashtag #NakedIsNormal, he wrote on Twitter: “Today we’re taking our identity back and reclaiming who we are.”

The “we” in that statement has been drooping steadily for years. After Playboy launched in 1953 with Marilyn Monroe as its centrefold, sales peaked in 1972 when the November issue featuring Lenna Sjööblom sold 7.16m copies.

In the decades that followed, the publication spawned an entire global empire synonymous with a certain kind of louche bachelorhood. There were clubs in big cities, a private jet bearing the bunny head logo chartered by icons like Elvis, and the famous Hollywood passion palace sex parties, presided over by Hef in his cult-leader robes.

Hugh Hefner at 40, in 1966. PA

The fact that his Bunny Girls were belittlingly trussed up like rabbits was a supposedly humorous nod to their penchant for frequent mating.

While never quite as gynaecological as its rivals during what were dubbed “The Pubic Wars” with more explicit magazines like Penthouse and Hustler, all roads to today’s on-demand hetero-normative online porn lead back to Playboy’s original efforts to naturalise it.

But by 2015, Playboy‘s annual circulation was just 800,000. Then, in late 2014, the editors relaunched the website as one that would be considered “suitable for work”. This was not to appease feminists, but to update its geriatric business model. And it worked. Viewings shot up 400%, from 4m unique views in July to 16m in December that year. The average age of site visitors dropped from 47 to just over 30.

The no-nude policy was extended to the magazine a year later. But Hef’s son, also no stranger to sporting silk pyjamas, reversed the move the moment he stepped up in the midst of his father’s failing health.

But given what’s on the web, it is not so much the parade of airbrushed flesh arranged carefully in stately homes that disturbs me. It’s the editorial ideology that surrounds these images of upscale masculine identity based on individualism, consumption and sexual pleasure without responsibility or commitment. If men are financially successful, the message appears to be, then they are entitled to consume luxury, whether that’s a Bugatti or a beautiful teenager.

Playboy defenders – and there are many – cite wearisome claptrap about how the magazine empowers women. Apparently many women work in Playboy’s editorial towers and the shoots are deemed a creative collaboration between the magazine and the model. With megastars like Kate Moss and Scarlett Johansson gracing the pages it’s got to be alright, girls, hasn’t it? Lighten up! It’s no different to when pop singers and film stars objectify themselves via social media.

But again, it’s about the patriarchal packaging. Successful female icons “doing Playboy” – a quintessentially male product – symbolically disarms the threat of women being successful on their own terms without the help of men.

Worryingly, the 2017 rebrand under more youthful leadership is peddled to younger men by featuring, somewhat creepily, a Harry Potter child actor in next month’s issue. It can be no coincidence that Scarlett Byrne, who played Patsy Parkinson in the trilogy, is to pose alongside an editorial entitled “The Feminist Mystique”, extolling the virtues of female nakedness for the male gaze. This also overtly sticks a finger up to Betty Friedan’s powerful 1963 work The Feminine Mystique, embraced by second wave feminists.

With a virginal-looking ingenue gracing the first nude issue in over a year, Playboy’s latest iteration of its elderly editorial imperative eases any tensions around gender blurring in the age of transsexuality, gay marriage and co-parenting. Men, you can feel appeased that your masculinity isn’t in crisis. The Hefner brand proffers a space where men and women have naturally different roles and functions and should adhere to ensure the smooth running of the social order.

Women, amid the barrage of conflicting signals about who we should be, can find our natural uncomplicated home in lingerie, with men who won’t try to demean us by putting a ring on our finger. Because, it seems that for some, although women can be more than wives and mothers, their primary purpose is still to be of service to men’s pleasure. It’s just another form of female domesticity outlined by Friedan, with the Hefner mansion the ultimate temple, peeling and moth-eaten but with a strong padlock on the front door.

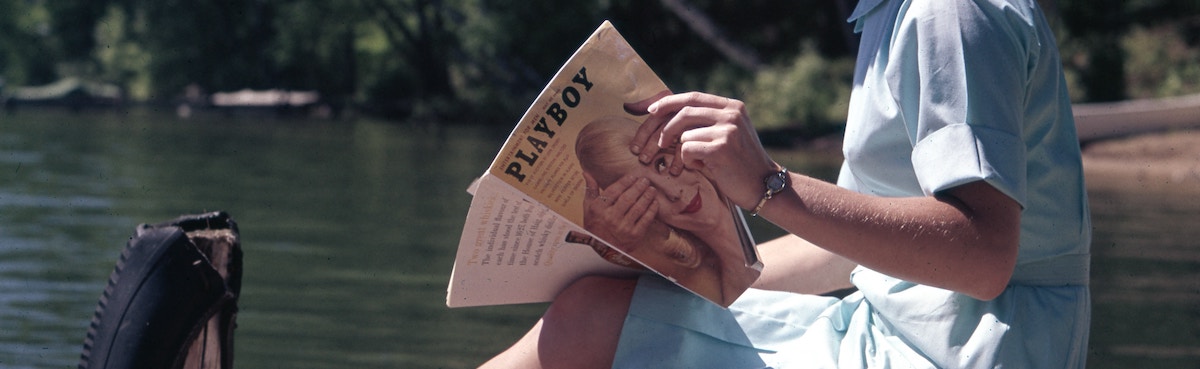

Photo by Les Anderson on Unsplash