This article is based on a year of conversations and work with Javier Espinal, an Indigenous Lenca artist, who travelled to Europe in 2015 to highlight the injustices in Honduras and to share the process of Muralismo.

To understand art, and the motivations of artists such as Javier Espinal, we must first understand the conditions from which it is born. In 2009 a military coup deposed the democratically elected president of Honduras and put in place a right wing junta. Since this time the country has descended into being the murder and repression capital of the world. Highly suspect elections, supported by many Western nations, have since consolidated the Right’s power, while presenting an illusion of democracy to the international community. Resistance to the neoliberal regime has been fierce, but has been met with equally fierce rebuttals. This violence has been used by the authorities to justify the militarisation of the country. The regular police have become secondary to the expanding ‘Tigres’ military police, who now roam the country from cities to the campo armed with assault rifles.

A sense of hopelessness has descended across much of the country as unemployment spirals out of control. In cities such as San Pedro Sula gang culture has taken over. Drug cartels are able to offer young people a role, and status, and their injections of money have fuelled yet more violence. This despite the proposed benefits of Honduras becoming a free trade haven. Multinationals have poured into the country since the coup, especially from the extractive industries – logging, mining and increasingly damming rivers to export hydroelectric energy. In the last couple of years a staggering near 30% of the country’s land area has been sold as mining concessions. Meanwhile, Honduras’ so called ‘model cities’ project may be the greatest sell out of national integrity seen in the world – selling large areas of the nation into corporate hands, to be run as semi-independent cities with their own rock bottom taxes, salaries and labour standards.

This is the reality of neoliberal, free trade-based macroeconomic development. International corporations provide so called ‘investment’, while employing as few local people as possible, at the lowest wages possible. They invest as little as they can, while sucking out resources and produce. This process, fuelled by corruption at the highest levels, is the reason for the descent into violence since 2009. Yet those who speak out against these economic adjustments, or in defence of human rights and the environment place themselves at increasing risk of execution and disappearance.

Despite the hopelessness in some quarters, the stoic resolve of the Honduran people continues to resist and fight for their rights and dignity, a pattern seen across Latin America in the face of the neoliberal onslaught. One such way that the resistance to the coup manifests itself is through the use of collective art projects, a process known as muralismo. Throughout 2015 we were privileged to spend time with Honduran artist Javier Espinal as he worked for ten months across Europe highlighting the plight of the Honduran people and working on collectivist art projects. This short article explores the integralist ideology behind his work and what this means for resistance movements both in Honduras and here in Europe.

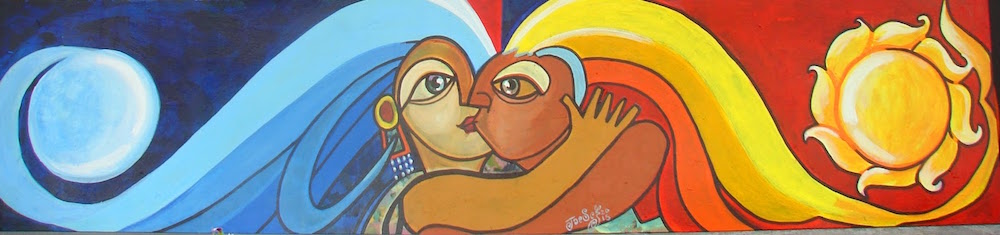

Integralism is a tradition according to which a nation is an organic unity. Integralism defends social differentiation and hierarchy with co-operation between social classes, transcending conflict between social and economic groups. For Javier, and the Lenca peoples, integralism is a spiritual position, ever present in Central American indigenous culture, which says that human individuals, animals and the natural world are all diverse and different, but are all linked to each other and are all equally important. Javier’s collective mural painting started in Honduras where he is from, and from where there is a strong tradition of muralismo that tells local stories and empowers communities and individuals. This tradition is also present across Central America, a region that has been faced with violence from both without and within throughout much of its modern history.

Integralism celebrates each of us as ourselves, as important actors, contributing to the diversity of the universe. We are equal with each other, and we are equal with the rest of the universe that we share. Javier’s description of Integralism sees people each as individual colourful and distinct threads, but each one woven together into the fabric of the universe itself. Individually we are bright and equal parts of the whole, but we go together to make up this iridescent multi-coloured tapestry. We’re distinct from one another, but we all rely on each other and the universe, of which we’re part, for support.

It is this deep-rooted and embodied sense of equality, diversity and sharing that informs the collective nature of Javier’s art. Collectivist art for Javier involves a whole community in its creation. Generally producing large murals in open public spaces, the community – including people just passing in the street – are invited into the shared space to take part in the painting. The creative process of the work itself was also a collective work in itself.

Javier’s work was not art just for the sake of art. His work forms part of a vibrant resistance movement, which has continued to grow since the 2009 coup. The process of painting and creation of such murals can, he says, “serve as a form of subversive dissemination of resistance themes”. They express the assault by the oligarchy and their military support on the indigenous and cultural heritage of Honduras. Yet, by expressing this through art they go under the radar of the authorities – becoming a form of resistance “hidden in plain sight”. They serve as a tool of empowerment and a rallying point for communities against the authorities.

While the finished art works themselves may not depict the kind of strong anti-regime sentiments seen in the Zapatista tradition, it is the process in itself that is the protest. The collective act of muralismo is about reducing the sense of alienation, and actively brings people into its process and makes them a part of it. Javier laments the alienation created by the Honduran ruling classes, “people are no longer connected to their surroundings, or their own culture”. This kind of enforced alienation is used as a further weapon against the people. It supports people’s ignorance and apathy towards global economic injustice and destruction of the environment.

While the situation in Honduras is one of pure desperation on the part of many, the parallels between events in Europe and Honduras were as clear to Javier as they were numerous. The same forced alienation that feeds apathy in Honduras breeds hatred toward foreigners in Europe. This manifests itself both in our own communities and without – the so called refugee crisis and the rise of right wing political groups are just two ways in which the ugly face of alienation rears its head in Europe – a situation likely to get worse before it gets better as the bitter war in Syria continues to displace yet more civilians causing a humanitarian catastrophe on our doorstep. This kind of alienation forms a backdrop to our current Western society, leaving us impotent to change.

Javier highlighted these parallels as he worked with communities in the UK, Italy and Spain. As he does with his work in Honduras he aimed to support communities in being strong in their own sense of identity, to fight this alienation. Through unearthing local stories – such as the Victorian era train track that runs through Irlam in Manchester – the murals give people both a sense of identity within themselves, and within their communities. He said he found this harder in Europe than in Honduras. “In Europe people didn’t think they’d be able to be artists” he said. Javier felt this was part of the loss of our sense of creativity or connection to the universe – the loss of a sense of integralism, which has come about through Western Individualism and Fatalism. In this he felt strongly that the Western culture has lost something, something that Indigenous Central American art can help us see again.

Integralism expresses an important alternative to what is happening in both Honduras and in Europe. In Honduras his art offers alternatives to youths and communities otherwise seemingly doomed to being ensnared in gang warfare and militarisation. His indigenous message offers a spring of resistance against the economic exploitation and military repression that supports this violence, creating hope in a country under the thumb of a rich elite and global business interests. In Europe it helps to arrest the alienation that closes us off from one another, and takes away our hope that there are alternatives to what we are given. Important as we are increasingly faced with a right wing political and economic message that says that there is no alternative to their agenda, that there is no alternative to Austerity, to the erosion of our rights, to the loss of democratic power to big businesses as seen in free trade agreements like TTIP.

Resistance in Honduras continues to grow, the Indignados have unquestionably changed the face of Honduran politics through 2015, but the military and Tigres continue to be used to suppress local resistance to expropriation of resources for the country’s rich and for selling onto the global market. As rivers are dammed, forests logged, land sold off, a desperate population is pushed into the hands of gangs, and those who resist are silenced. The resulting militarisation plays into the hands of the economic and social elites of Honduras. Javier and many grassroots organisers in Honduras believe that the corrupt authorities support the gangs in places they want to control with terror – not dissimilar to the way in which the war in Colombia has been used in recent years.

The message that Javier and the integralist and collectivist tradition of Honduran and Lenca protest art brings is one of strong community spirit, of an integral and equal value to all of us alongside nature and the universe, and seeks to empower us. Javier’s time and work in Europe has served as a point of contact between our countries. His work and the Indignados movement in Honduras reflect just how powerful we can be, together – we must resist alienation, be it through military oppression in Honduras or divisive political rhetoric in Europe. We are each a “colourful and distinct thread, but we are all woven together into the fabric of the universe itself”. Integralism and the Lenca tradition remind us that there is an alternative. It is we, the masses, our communities, the grassroots organisers and the artists – WE are the alternative.