Inform, entertain, and… as the school year begins again, it’s a good time to delve into the history of the BBC as an educator.

BBC School Broadcasting was the part of the BBC that produced television and radio programmes for use in school classrooms. Many will remember dancing to Music and Movement, or the television trolley being wheeled in for Look and Read. In fact, broadcasting formed a vital part of the national education system, and by 1970 the BBC was producing 114 separate series for schools, and over 90% of schools were tuning in.

Margaret Thatcher became Secretary of State for Education in the new Conservative government of 1970. She was worried that BBC School Broadcasting was criticising marriage and promoting communism. In the late 60s, programmes for sixth formers, such as Scene and Inquiry, had started exploring complex social issues – but the BBC had a protection mechanism.

BBC School Broadcasting was unusual in that its programmes were not instigated by the BBC itself. Instead the School Broadcasting Council (SBC), a panel of teachers and educationists, used their expertise to identify educational priorities, and ‘sponsored’ the resulting programmes. The SBC membership was appointed by educational institutions, and the Department of Education and Science (DES) was allotted two appointees. It always chose a senior school inspector (HMI), and a civil servant from the department.

Secretary of the SBC John Robson, was therefore surprised in July 1971, when J Banks, Thatcher’s Private Secretary informed him;

‘The Secretary of State has considered this matter carefully and has invited Mr Bryan Forbes to be one of her nominees on the Council, and he has accepted.’

Bryan Forbes was a famous actor, screenwriter and film director, who had been nominated for a BAFTA for directing Whistle Down the Wind in 1962 and had recently greenlit The Railway Children as head of EMI studios. He probably met Thatcher while filming Conservative party political broadcasts. The two apparently hit it off, and Forbes referred to Thatcher as ‘streets ahead of other Tory MPs in intelligence’. Forbes was of course not part of the DES, nor an educationist of any kind.

Bryan Forbes directing Play for Today, 1980

Bryan Forbes directing Play for Today, 1980

Robson balked at this politically motivated interference, and trampling of precedent. How could Forbes represent the educational expertise of the DES? Robson first telephoned Banks to ask him to reconsider. Banks was prepared, and the ensuing argument hinged on the wording of the SBC’s constitution. Quoting from the constitution, Banks argued that ‘…‘a representative of the DES’ can only mean a person who serves with the approval of the Secretary of State…’.

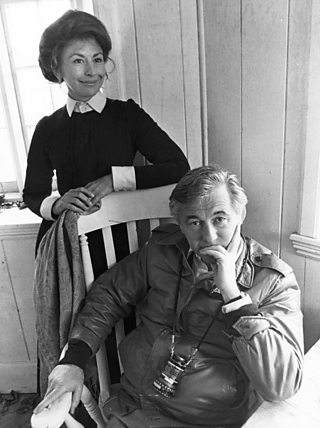

John Robson, 1969

John Robson, 1969

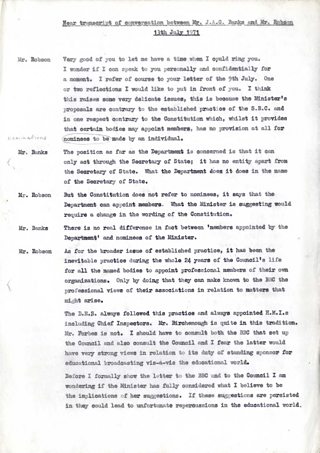

Robson argues with Banks, 13 July 1971

Robson argues with Banks, 13 July 1971

Robson turned to the SBC Chairman Charles Carter, who replied ‘This is a fight we cannot win.’ So, Forbes and M. Birchenough (who was an HMI, as normal) were appointed.

Robson Counters

Robson fell on a new strategy. He knew, although would not have admitted so, that the SBC had very limited real control over BBC School Broadcasting. Actual programme making was the preserve of the school producers – whose proposals the Council almost always approved. The real value of the SBC was to legitimise the BBC in schools.

However the SBC also had a ‘Steering Committee’, which made decisions about overall policy, and in some ways had more power than the council. Access to this was controlled by the senior SBC staff, who had left it to Robson ‘to invite one of the DES representatives on the Council’ to serve on it. Robson rang Birchenough and invited him.

But Birchenough told Robson that he would not be allowed, and said confidentially, that he was

‘…somewhat unhappy about his position… and that he would not be able to accept a situation in which he was expected to act as the Minister’s Censor.’

Birchenough duly reported to Thatcher, who indeed refused him permission and sent Robson another official, Elliot, who made it clear that she wanted Forbes to join the Steering Committee. Nevertheless, Robson was determined to resist – and still had room for manoeuvre.

Again swerving Forbes, he asked Mr. Wynne Lloyd to be on the Steering Committee, who was also an HMI on the SBC – but as an appointee of the Welsh SBC (Wales and Scotland had their own Councils). Technically he fitted the bill, as a ‘representative of the DES’ – but as a member of the Welsh Education Inspectorate, he was free from Thatcher’s control.

Forbes attended his first SBC meeting in December 1971, and was unimpressed. In a memo on the episode, Robson relates that Forbes afterwards took him aside to say;

‘…he thought Mrs. Thatcher had made it clear that she wished him to be put on the Steering Committee. He didn’t feel that he could serve any useful purpose on the Council which was ‘merely a rubber-stamping body’’.

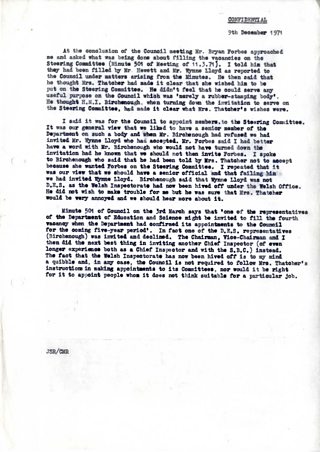

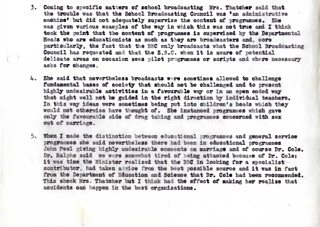

Robson meets Forbes, 9 Dec 1971

Robson meets Forbes, 9 Dec 1971

The Minister is Placated

The Chairman (by then Elfed Thomas), Vice Chairman Lincoln Ralphs, and Robson later met Thatcher and her permanent secretary in February 1972, and cleared the air.

Margaret Thatcher as Secretary of State for Education and Science, 1970

Margaret Thatcher as Secretary of State for Education and Science, 1970

Thatcher expressed the view that

‘…broadcasts were sometimes allowed to challenge the fundamental bases of society that should not be challenged.’

But apparently had little real knowledge of BBC School Broadcasting, and her objections were dealt with easily by Thomas and Ralphs. Their control over the Steering Committee was retained.

Thatcher meets the Chairman, Vice Chairman and Secretary of the SBC, 14 Feb 1972

Thatcher meets the Chairman, Vice Chairman and Secretary of the SBC, 14 Feb 1972

The minutes of the two SBC meetings that Forbes attended do not record any contributions by him. In his memoir, A Divided Life, he refers to it as ‘an unwieldy body that pontificated at length and achieved very little.’

As for Thatcher, her memoir hints that Birchenough’s discomfort was shared by other DES staff, recalling of her time there that ‘I was not among friends.’

The relevant files in the BBC archives are testament to a remarkable, even over-confident resistance to government interference – and a time when BBC School Broadcasting was worth fighting for.

Steven Barclay is researching a PhD on the History of BBC School Broadcasting and Progressivism in Education, at the Communications and Media Research Institute (CAMRI) at the University of Westminster. He has worked as an editor of educational film. His current research explores the history of media policy, television and radio as a public service of education, educational media and publishing, and language and communication.

stevenbarclay@my.westminster.ac.uk

https://camri.ac.uk/blog/staff/steven-barclay/

Image: Wikimedia Commons. The Thatcher Estate, the copyright holder of this work, allows anyone to use it for any purpose including unrestricted redistribution, commercial use, and modification.