The coronavirus crisis brought an upsurge of local and neighbourhood organising in the UK. In the beginning of March, when coronavirus cases started climbing and lockdown was looming, COVID-19 mutual aid groups started cropping up in different parts of the country. According to their national website, there are currently 4,225 such groups across the UK, covering both rural and urban areas.

The groups are formed by neighbours coming together to help those self-isolating in their area due to coronavirus. Neighbours run errands for those who cannot leave their homes, including dog walking, picking up shopping and prescriptions, posting mail or paying bills at the post office. They also make friendly phone calls to those who may be feeling lonely and anxious in self-isolation.

This type of community organising is often considered apolitical as it aims at offering relief of people’s immediate needs rather than at changing government or corporate policy. Of course, the reality is much more complex than that as caring for the community can build alternative social relationships and change dominant ideas about how society works.

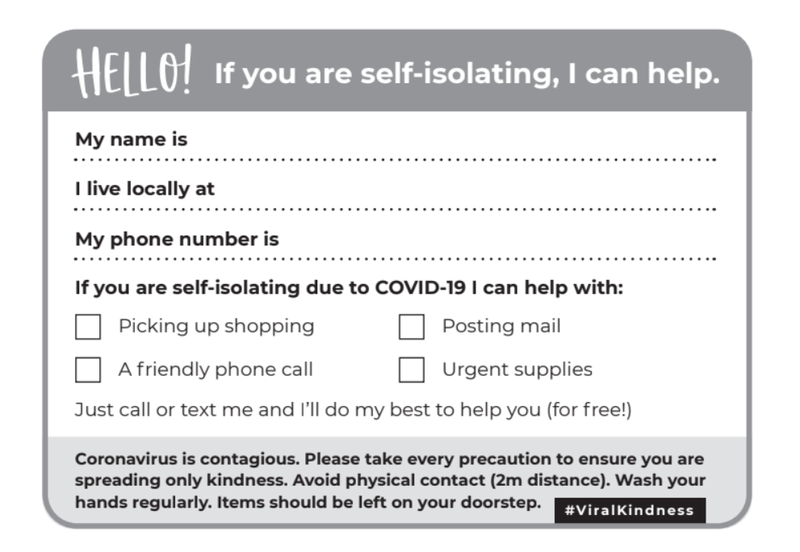

Template leaflet. | MutualAid. Some rights reserved.

Groups that ascribe to the notion of mutual aid have this potential, as mutual aid operates outside formal frameworks and places the emphasis on horizontality and equality. As the UK COVID-19 mutual aid website notes:

“Mutual aid is where a group of people organise to meet their own needs, outside of the formal frameworks of charities, NGOs and government. It is, by definition, a horizontal mode of organising, in which all individuals are equally powerful. There are no ‘leaders’ or unelected ‘steering committees’ in mutual aid projects; there is only a group of people who work together as equals. Mutual aid isn’t about “saving” anyone; it’s about people coming together, in a spirit of solidarity, to support and look out for one another.”

This has the potential to transform social relations and lead to deep shifts in political culture.

Of course, this more political understanding of mutual aid is not necessarily embraced by all the community groups that have registered themselves on the platform. For some, this may simply be a way to help vulnerable neighbours in a spirit of charity, which implies a more hierarchical relationship, where the ‘helpers’ are more powerful than the people they help.

I will come back to the political potential of COVID-19 mutual aid groups at the end of this article, after I provide more detail on how they organise and how they use digital media to do so.

.

Mutual Aid Groups and hyperlocal digital organising

It is difficult to identify the exact date when the first COVID-19 mutual aid group was created in the UK, but many of them were established around the 10 to 15 March 2020. There were call outs on Facebook and Twitter for people to launch a group in their locality by setting up a Facebook page or a Whatsapp group. People could then register the links to their Facebook or Whatsapp groups on a list initially compiled by Freedom Press, that runs Britain’s oldest anarchist press and magazine and its largest bookshop. Common Knowledge, a cooperative that designs digital tools for radical change, soon incorporated this list into one compiled on software tool Airtable and then collaborated with volunteers from the UK national website, who had been doing their own data gathering, to create one unified list of all registered groups. These volunteers produced software that allowed visitors to the UK mutual aid website an easy way to find the group operating in their area.

But how were these localities defined? How did participants decide on the boundaries of their neighbourhood, particularly in large cities such as London? The maps of electoral wards were very useful in this respect as they allowed participants to use a ready-made framework for designating localities: the definition of mutual aid groups was based on the electoral geography of the UK.

Still, many groups servicing large electoral wards decided to break into ‘micro-groups’, focused on smaller neighbourhoods of the ward or even on specific streets. This is because, as the organising of mutual aid groups took off, participants realised that smaller is better: ‘micro-groups’ could get to know the needs of their specific area in granular detail and facilitate relationships between close neighbours. In areas where people did not know their immediate neighbours, this helped to establish trust as admitting your vulnerability and requesting help from strangers can be very challenging. Geographical closeness helped to moderate this fear.

.

The digital infrastructure of mutual aid groups

The move to micro-groups was also dictated by the technology employed for organising. Whatsapp was one of the main organising platforms. Neighbours used it to create specific Whatsapp groups for those requesting help, for volunteers, for organisers, and for a host of activities, such as coordinating the phoneline or dispatching volunteers. However, with Whatsapp groups being limited to 256 members, it was impossible for large wards to use Whatsapp for incoming requests in a way that covered most of the ward. Micro-groups were a solution to this problem.

Whatsapp provided many benefits for organising. Employed by 73% of internet users in the UK, it is a widely accessible application. Whatsapp also allows the quick exchange and forwarding of information, and messages have end-to-end encryption. Groups can be public, and people can join simply by clicking on a link or by scanning a QR code.

However, Whatsapp is not a platform built for organising. New members of the group do not have access to previous discussions, obliging admins to post a ‘welcome message’ with useful information about the group every time a new member joined. The speed of posting led to information overload, which meant that useful information could be lost in the flow. Information overload can also increase the risk of burnout, as members become overwhelmed by the volume of messages and are constantly interrupted by notifications. The Whatsapp chat also included information that was not relevant to organising. Members were often reprimanded for engaging in small talk, while, in some areas, groups created Whatsapp spaces for general discussion to direct the chatter away from the groups used for practical tasks.

Participants began to employ other platforms that are more suitable for organising, such as Slack, built specifically for project coordination. The digital infrastructure of mutual aid groups also included Zoom for calls involving organisers and volunteers, Skype for operating help request phonelines, and various Google apps: Gmail for the email address of the group, Docs for the minutes of meetings, statements and guidelines, as well as Sheets and Forms for compiling databases of volunteers and requesters and for recording information about pharmacies and shops in the area. In other words, the digital infrastructure comprised some of the most widely used applications for project work.

Despite the use of such proprietary applications by some local groups, it is worth noting that all of the software behind the efforts of the national coordination, including the website, is open source. The team involved have also been co-ordinating internationally to create the necessary resources for mutual aid groups. This international coordination has generated the initiative Mutual Aid Wiki that, according to its website, enables “mutual aid communities to find each other, share approaches and support one another.”

The groups also had to use physical media, such as leaflets and posters, for reaching people with low internet connectivity or digital literacy. They undertook mass leafleting in people’s homes and put up posters in shops and in the street. There were of course concerns about the risks of spreading the virus through such physical media. Thus, groups developed detailed guidelines about leafleting to ensure the safety of both volunteers and those self-isolating.

National coordination occurred through the UK COVID-19 mutual aid website that was set up to gather information and resources about these groups. One administrator per group could also participate in a closed Facebook group to exchange ideas and tactics. Yet despite these more organised efforts at national coordination, the learning and diffusion of information mainly occurred in a more organic manner as members would follow neighbouring groups in Whatsapp and cross-post useful content. Information diffusion was quick but having some basic resources on the national website as early as possible would have speeded up this learning process even further.

.

Two models of organising: Mutual Aid Groups and the NHS Volunteer Responders Service

The decentralised organising model employed by mutual aid groups becomes clearer if we compare it with the more centralised NHS Volunteer Responders scheme. The latter was set up by the UK government and the National Health Service (NHS) to help those registered as vulnerable by facilitating volunteers to undertake similar activities to those assumed by mutual aid groups. The NHS stressed that this service was not meant to rival what local groups and charities were already doing. Indeed, while some of their activities did overlap, the two models were also complementary as they were not servicing precisely the same users.

This is because the NHS scheme was launched to help the 1.5 million UK inhabitants who are registered as vulnerable. For people to request help they needed to have this formal registration or to be referred to the service by their doctor. This excluded people who were unwilling to register formally, for instance, because of their immigration status. By contrast, mutual aid groups cover everyone who is self-isolating, whether they are formally registered as vulnerable or not.

Poster on Hackney MutualAid Facebook page. | All rights reserved.

One of the key differences between the two models is speed. The NHS scheme was announced by the government on March 24, a full two to three weeks after the launch of mutual aid groups. The scheme had an initial target of 250,000 volunteers, but, within a few days, 750,000 people had registered, so the service stopped accepting new applications as it could not process them quickly enough. Volunteers also complained about delays in getting assigned to tasks, sometimes having to wait for more than two weeks after they applied to the service. As a centralised and formalised system, the personal details and identities of volunteers had to be carefully checked. Conversely, the informal nature of mutual aid groups, which are not a legal entity, meant that they did not engage in the verification of personal details, a feature that enhanced their speed but potentially decreased their safety. The NHS scheme also had to handle a very large number of volunteers in relation to the local mutual aid groups that are much smaller, and thus nimble and agile.

The NHS has partnered with the GoodSAM application to deliver the service. Volunteers need to register with the application, and they receive requests for help through the app. Here a key difference arises between the centralised and decentralised approach in the handling of personal data. While both work in accordance with GDPR rules, the mutual aid groups were advised by the national coordination website not to keep any personal data. Some of them do temporarily retain some information on requests for help and on volunteers, with guidelines about deleting data when they are no longer necessary. Data are accessible only to a few volunteers – in the Shacklewell ward group that I am involved in it is only those who run the dispatching service who have access to this data. By contrast, the GoodSAM app has access as ‘joint controller’ to the names and email address of all volunteers registered on the service. Users also submit data directly to GoodSAM when they use the app, of which GoodSAM is the ‘sole controller’ and agrees to use the information according to its own privacy notices. This points to two different logics of data management: one that decentralises the information to informal groups that have access to the data of only a small portion of the total population; and another, in the case of the NHS Volunteers, that centralises the information to formal groups, both state and corporate actors, who retain access to all or some of the data pertaining to the whole population.

With the current development of track and trace applications, thorny questions are arising with regards to the second model, particularly around the increasing capacity of corporate actors to utilise the large-scale information compiled by the state.

A final difference refers to how care is viewed. As mentioned earlier, although not all COVID-19 groups embrace this ideology, mutual aid refers to equal and horizontal relationships of solidarity. Conversely, the NHS volunteer responders scheme follows the more hierarchical model of charity as it makes a clearer distinction between those who are vulnerable – and registered formally as such by the state – and the volunteers who help them.

.

Conclusion: community resilience and political implications

Mutual aid groups have created a hyperlocal infrastructure of care that includes diverse digital platforms and applications, as well as physical media such as leaflets and posters. Members of these groups have also developed common organising practices and social norms. The interpersonal relationships fostered between neighbours who need and receive help can go across generational, racial, gender and political divides, depending of course on the diversity of each locality.

The functions of these groups are evolving as the UK moves to a different phase of the coronavirus pandemic. In our Shacklewell group, possibly also because of the launch of the NHS scheme, the number of requests for help has fallen in the past few weeks. So the group has branched out to other activities, such as supporting our local foodbanks. A key question here is whether, with time, the groups will shift from tending to the immediate needs raised by self-isolation to the more enduring projects of community resilience around COVID-19.

As the coronavirus crisis is becoming politicised, these groups may also get more involved in political campaigns that address the broader impact of the pandemic. The economic fallout of this crisis is expected to generate a wide range of campaigns on unemployment, homelessness or housing. It also highlights class, gender and race inequalities, as COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting minority ethnic groups and those living in deprived areas.

As the multiple aspects of this crisis unfold in the months and years to come, will this hyperlocal infrastructure be used for mobilising around these different campaigns? Elements of this are already visible. For instance, on May 24 activists associated with COVID-19 mutual aid groups staged a die-in outside the house of Dominic Cummings, a senior advisor to the prime minister who has been accused of breaching coronavirus regulations around social distancing. At the time of writing, when Black Lives Matter protests are taking place all over the world, information about how to support BLM is circulating in COVID-19 Whatsapp groups. There is also the question, a bit less interesting in my view, of how these mutual aid groups can influence local elections and local government.

As a hyperlocal infrastructure of care, COVID-19 mutual aid groups revolve around caring for neighbours. This care may take many forms as needs change, but one thing is for sure: by strengthening the relationships of people living in geographical proximity, the problems of health, isolation, discrimination, unemployment or housing are no longer experienced as abstract societal issues, but as local realities that are affecting someone you know personally. This can have a powerful impact on political mobilisation and social transformation.

Photo by Daniel Schludi on Unsplash