Considered one of the UK’s advertising’s ‘inspiring minds’ (History of Advertising Trust, 2018) creative director, copywriter and author Dave Trott has worked on iconic campaigns for the likes of Toshiba, Holsten Pils, Ariston and Pepsi and with agencies including Gold Greenlees Trott, Bainsfair Sharkey Trott, Walsh Trott Chick Smith and latterly The Gate.

As well as consumer product campaigns, Trott has also addressed social issues via advertising, notably on malaria and cancelling third world debt, championing challenging conventional thinking in doing so. A believer in using shock tactics, standing out and treating the consumer intelligently with bold and simple creative ideas he is the author of four books (2009, 2013, 2015, 2019).

For WPCC’s issue on ‘Advertising for the Human Good’ issue editor Carl W. Jones asked Trott to consider the potential of advertising for the human good with wide-ranging answers given on major questions: should advertising have such a role?; is university education a hinderance to creativity; and whether much of advertising can be considered ‘pollution’.

Keywords: Advertising; Third World debt; creativity; social issues; advertising practice; race; class

Carl Jones in Mexico City interviewed Dave Trott in London via Zoom software 23 June 2020. 10am CST, 4pm BST.

Carl: First of all, it is a pleasure Mr David Trott to be interviewing you for this special edition journal. In this interview I wanted to examine various topics that my colleagues have touched upon in their research. The first is ‘race’. When you started in advertising in the late 1960s how were races or ethnic groups usually represented in say print or TV ads?

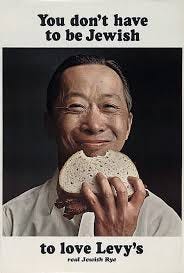

Trott: What everybody did in the UK was copy the American creative leader Bill Bernbach owner of advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB). So, before him advertising usu-ally just had perfect looking white people. Then the agencies started to remove good look-ing models from the ads and replacing them with characters with a more ethnic look. In the 1960s is when the change happened in New York advertising where different types of models, including more ethnic looking ones were used. I saw it and thought it was fantastic, you know using people’s ethnic background in the advertising, and claiming it for yourself. It was really an amazing opportunity (Figure 1). So, when I went back to England, I thought I’m going to do that in advertising. The way Bernbach had used different ethnicities such as Jewish people, Asians, or Italians, to advertise a bakery. So, what I did when I came to the UK was use cockneys and claim it for me.

It worked brilliantly. And it is important to remember that brands shouldn’t want to be doing whatever everybody else is doing, because if they do, then only the market leader can win. So, if you are a small beer and do the same advertising as Budweiser, then you lose as everyone will think it is the same ad, it’s better to differentiate yourself. Stupid marketers copy what the market leader is doing and that confuses your brand with the market leader and your brand disappears.

Figure 1: Not perfect looking white people. Magazine campaign for Levy’s. (DDB 1961–1970).

Carl: Dave, do you remember any impactful campaigns that changed the way marketing was performed?

You know most people don’t understand the difference between ‘market growth’ and ‘mar-ket share.’ Market growth only the brand leader can do, vs. market share is what you have to do if you are not the brand leader, by taking share from the brand leader. You need to have a message that says I’m not the leader. Like when Bill Bernbach of DDB did with the American car rental company Avis, who were ‘number 2.’ against the market leader Hertz. If you ever want to teach anybody a case history it is the Avis against Hertz campaign. The main message was ‘Avis is only №2 in rent a cars. So why go with us? We try harder!’ (Figure 2). Now Avis can’t say that any more as they’re both number one in the USA.

Figure 2: Being different, trying harder– Avis print ad. (DDB 1962).

Carl: In my experience as an ad practitioner for over 25 years, and recently I decided on a career change into research and teaching, and upon entering the world of academia I noticed that most academics tended to criticise advertising as something that puts the con-sumer into debt, and manipulates them into spending money unnecessarily. Do you think advertising should take responsibility for improving society, or is that the government’s job?

Trott: You have a lot of things in that question, I will answer it by focusing on three points. Also, I’d like to mention that I’m not the spokesperson for advertising. I believe that 90 per cent of advertising is garbage. Done by stupid people and it is pollution. But 10 per cent of advertising that is good, is absolutely brilliant, and is a positive contribution to everybody. Because, it’s fun and people love to have it in their lives. Consumers remember the ad jingle and sing it. Talk about it on buses. Even repeat the strap line (tagline) etc. It’s a good contribu-tion to society like a good sitcom can be. Most people who work in advertising are too lazy to create memorable messaging, they just care about the money, or some award at the Cannes ad festival, and drink some champagne, and buzz around the sea on a yacht. That’s rubbish. But then … that’s not just advertising, that is the world we live in. Ninety per cent of the world is rubbish.

That’s point number one. You can’t defend advertising. Like you can’t defend architecture.

Ninety per cent of architecture is rubbish. Every council estate (social housing) you look at is rubbish. Yes, there are some great buildings in the centre of London. You know the Chrysler building in New York is fantastic. The Gherkin and Lloyd’s buildings in London are beautiful things. But 90 per cent of architecture is pollution. Because it is done on the cheap by councils and it’s a waste of time done by people who can’t be bothered. Who in fact don’t know the difference between good and bad architecture. That is the same with everything. People who design cars, packaging, shops. Ninety per cent of the world is rub-bish. But the 10 per cent left is fantastic, and it is also impossible to see that 10 per cent in your own life time. That’s why I don’t spend a second with anybody that I don’t respect. Because I’ll never get to see the 10 per cent that is great if I’m with the 90 per cent that is rubbish.

I’ve only spent my advertising life in the top 10 per cent. I didn’t realise that until five or so years back. When I had to merge my agency with another one, and it was the very first time I had to work with an agency that wasn’t very good. I didn’t believe how stupid the people were. It’s kind of like Bobby Moore who was Captain of England football (soc-cer) team, the only time England’s ever won a World cup, was due to Bobby Moore and he was the best footballer we ever had. He thought that after finishing playing football, he would become a manager, so in 1979 he decided he would start managing the Southend football club. What he suddenly realised is, ‘Southend is the dregs’, ‘these are players who you wouldn’t even consider asking to clean your car boot (trunk)’. That’s exactly how I felt, I didn’t even know that there were people that bad in advertising. The only people I’ve ever worked with are the top 10 per cent. I have been competing with the best. David Abbot; John Webster; Paul Arden; and Charles Saatchi, some of the UK’s best advertising people.

I took all of my time to compete with those top guys, and I didn’t even think of anybody outside of that exclusive group. As it turns out there is the little peak at the top in advertising, and the rest is just crap. (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Dave illustrates a triangle with his hands showing the ‘peak’.

Carl: And your second point?

Trott: Is advertising good, or is it bad because it encourages consumption? They were saying that in the 1960s when I started to work in advertising. How dreadful advertising was and how it encouraged people to buy stuff they don’t really want. My answer is, well don’t make it. All advertising does is tell the consumer that it’s there. It is not hypnosis. Ads tell you the product’s there, and if the ad’s any good, then it will tell you in a funny or interesting way. If you’ve got the money and you want it then you’ll buy it, and if you don’t have the money, then you won’t. Look at it this way, you’re an adult and you’re responsible for what you do.

Point three, advertising for good. This is where people go wrong, advertising isn’t market-ing. Marketing is marketing and advertising is the voice of marketing. I don’t do marketing. Clients do marketing, they create a product and then decide how it is sold. Then the client decides where they are having the distribution, what size they will make the product. What colour it is, and all the rest of it. Now once you’ve got your product made, you need to get it heard about, then it’s my job (to advertise it).

The numbers are that in the UK over £20 billion are spent on advertising and marketing every year (Statista, 2019). Of that let’s say four per cent of advertising messages are remem-bered positively, seven per cent are remembered negatively, and 89 per cent are not noticed or remembered. So that is roughly £18 billion pounds wasted by people who don’t know what they are doing. So, if you don’t notice it or remember it, then it is money wasted, it’s just pollution. It’s my job to get you as a client to be part of the four per cent that is remem-bered positively, or the seven per cent that is remembered negatively, or at least in that 11 per cent that is noticed and remembered. In the 1970s and 80s, the adverts were considered by the British public to be better than the TV programmes and they haven’t said that for 20 years. That’s because too many in marketing went to university and studied advertising as an academic subject, and learned a set of rules. When advertising was great in the mid to late part of the last century it was like the Wild West, and we had to out-think our competition. And not just do what got you good marks at university, not write a brief as if it was a thesis. Because everybody who went to university is doing the same brief, they learned the same things, obeying the same rules, so everything looks identical, and is in the 89 per cent that isn’t remembered. Because it all looks the same. This is not a difficult concept to understand, it is Gestalt. You know?

Carl: I’ve heard of it, isn’t it the school of psychology?

Trott: I like to think of it as the software that the mind works on.

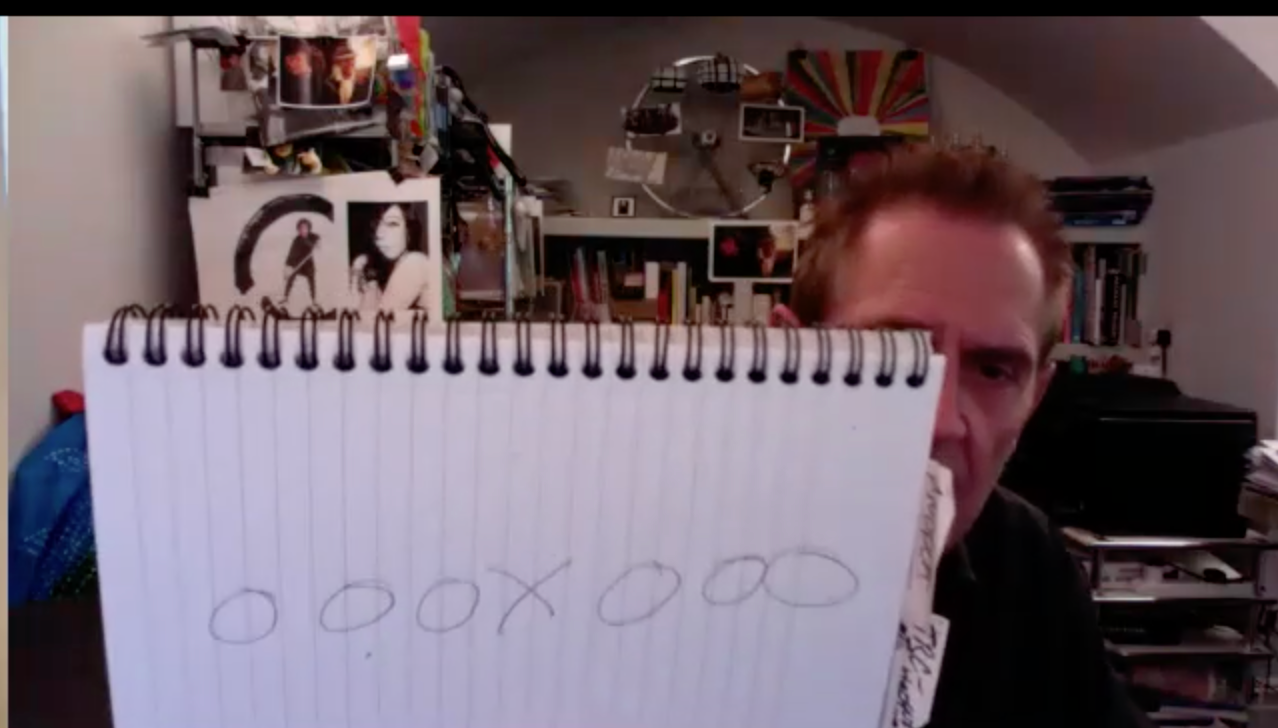

Here let me explain. Imagine this is an advert break, in the middle of a TV show, and it has seven adverts in it. (Figure 4. Dave draws on a piece of paper and shows six ‘O’s’ and an ‘X’. Then asks here are the seven adverts, which one did you remember?)

Carl: The ‘X’

Trott: Not difficult is it.? Why is that Carl?

Figure 4: Dave Trott representing TV ads with O and X’s via zoom.

Carl: Because the ‘X’ stood out.

Trott: The mind is a pattern making machine. The basic software you run on from the second you are born, your mind breaks things into patterns. What your mind does here is not see seven things, it sees two things, a bunch of ‘O’s and the one ‘X’ that isn’t like the O’s. You straight away have 50 per cent share, just by being different. Tell me the name of the 44th president of the United States of America? Normally people can’t. But when I say can you tell me the name of the first black president of America? And everybody knows it. Okay it’s the same guy. Obama. But when I ask you the 44th president, they are 44 identical blokes. When I ask you about what makes him different? Then you know who he is. Now that’s our job in advertising, is to take your prod-uct and make it the first black president, not just one of 44. Now I have half your mind, instead of 1/44th of your mind. That’s how I train kids. You start with Gestalt. Being different is good.

What everyone else is doing, you don’t want to do that unless you are the market leader. If you are Coca-Cola then do it, if you are Nike then do it. If you’re Apple then do it. If you are a brand that doesn’t own the market then you have to find out why you’re better than Coca-Cola, why you’re better then Nike, why you’re better than Apple! The smaller brands should ask themselves, why do they even exist and why should I as a consumer even care? That’s market share, and most products need a ‘market share’ argument, and not a ‘market growth’ argument.

Now back to my point three which I am going to explain in more detail. Advertising for good. My question is why? Why would you do advertising for the human good?

Carl: It is advertising that benefits humankind, for example that campaign that you worked on to eliminate Third World debt. It is not a campaign designed to get people to buy products that they don’t need, but to inspire people to help other humans. I would argue that your campaign is an example of advertising for the human good.

Trott: If you look at what Bill Gates does, vs. what I was doing. At my art school called Pratt in NYC it was a Bauhaus led art school in terms of thinking. Everything we were taught was based on how ‘form follows function.’ So, you start off with the function. And when you know the answer to that, then the form is dictated. Bill Gates, what he was looking for, after he made his money, he asked, what is the single most good I can do? That’s the question, what is the single most good I can do? Not I want to do some good for the planet. He found out that the single worst thing for the planet was malaria and mosquitos. He said right, that’s it. So, when you say why? That is the answer. Because he is the guy going after the thing that has killed more people than anything else. And when you ask me, why did I get involved in creating advertising eliminating the Third World debt, it was because, the Third World debt was killing five million little children every year. I don’t want to particularly make people feel good, or have a donkey sanctuary, in fact I’m not a warm person particularly. But five million children a year dying because of the Third World debt? (Trott, 2018). All because the local government couldn’t cancel the debt, and won’t cancel the debt. The banks will only cancel the debt if the all the other banks cancel the debt. No bank is going to cancel it on its own. All I had to do was use advertising, to get the subject into a conversation.

So now you’ve got really hard facts and action, instead of just ‘woolly’ oh I just want to do some good. Because why do you want to do some good? All this ‘brand purpose’ crap, with clients inserting it onto their campaign. Saying we must have some brand purpose stuff. So, the marketing departments try to ‘ladder up’ … they make their washing powder wash clothes whiter … then they ask … ’how will that make the consumer feel?’ The answer is ‘like a better mum’, that is followed by … ‘make you feel like a better neighbour.’ …then … ‘that will make it feel like a better contribution to the neighbourhood’ … oh and then …’it will make the world feel better.’ So now we’ve laddered up to the thinking that our washing power will make the world a better place.

Nobody buys washing powder for that. That is just stupid.

What the brand has done is slap this thought at the end, because they couldn’t be bothered in doing original thinking. They’ve used some technique that they’ve learned in a marketing course at university called ‘laddering up.’ How does coffee make you feel? ‘It wakes me up in the morning.’ How does that make you feel? ‘Well it makes the bus ride enjoyable.’ How does that make you feel? ‘It makes me feel good when I see everyone at work when I get there.’ How does that make you feel? ‘It makes work a better place, which makes the world a better place’ Ahh ok … then we can say our coffee makes the world a better place.

So now you have washing powder that makes the world a better place, then you have cof-fee making the world a better place. When you ladder up, you ladder up to the same thing, which is always we make the world a better place. Which is a meaningless nothing. Created by something that the client learned in a marketing course and asking ‘have you laddered up?’ Nobody is using their brain.

Form follows function. So, what needs to be asked is what is the job we have to do here? Why do we have to do something for the public good? If you have a reason then the form will come out of the function.

Carl: So, what you’re saying is that there are brands that only want to link something positive to their product through brand purpose or laddering up, and that isn’t messaging for the human good. However, for me, the campaign that you created asking to remove the Third World debt is an example of advertising for the human good (Figure 5).

Trott: Well OK, but that is not why I did it. I did it because there were five million kids dying every year.

Carl: Right, you are saying there are two ways of looking at advertising for the human good. One, is brands trying to appear that they care, and then two, there is human good advertising that is based on a real truth and need. Where form follows function.

Trott: When I went to … I think it was Lloyds of London who said to me … .well we could cancel the Third World debt, if the other banks could cancel it as well. And I said why haven’t you cancelled it? And he said, well I’m not entitled to cancel it, as it is my duty to look after shareholders’ interests. I can’t cancel it because I think it is a good cause. You may think the donkey sanctuary is a good cause. But if I cancelled £3 million pounds worth of that debt, I’d find myself in jail. He said, what you think is a good cause is subjective … and what I think is a good cause is subjective … so we can’t. So, when you say ‘for the human good’, it is subjective. Hitler has a different vison of human good than I do. That is my problem with the word ‘woke’ it’s a very one-way ‘human good.’

Let’s do the form before function here … let’s take human out of it, and put in something people can feel strongly about. Let’s look at Bill Gates again, I don’t think Bill Gates started out with human good. He started with where’s the one place where I can attach my power … and money and Warren Buffet’s money … that will actually make the biggest dent … on the planet. And the most benefit to most people? Certainly that is a real tangible question. Rather than human good. Which is really subjective and means ten different things to ten different people.

Carl: Dave, as well as creating many award-winning advertisements, you’ve written four books and just waiting for your fifth one to be published. Also, you’ve got the column in the UK adver-tising industry weekly Campaign. Do you think, that in like 50 to 100 years … what do you think will have the biggest impact on society … your writings or your advertising?

Trott: I don’t think any of them will. They will all disappear like smoke. Well certainly the one that will disappear will be the column in Campaign, because it talks to advertising people. It doesn’t talk to real people. The adverts I did were 20 or 30 years ago and they don’t run anymore. So, unless you are old enough to remember them, then they won’t mean anything. And the books, they are ok, and you know new books are coming out all the time. And people will need new things to replace the old books. So, I don’t mind, for me it is not about legacy. It is about putting your foot down now and make the biggest impact, as you won’t be around in the future, so don’t worry about it.

Carl: I saw your interviews online at the History of Advertising Trust (HAT) web archive, they are doing a really interesting job by trying to keep a record of everything done in UK advertis-ing, in fact they have the largest collection of advertising in the world, it also includes a lot of your work. Another supporter of advertising is the Canadian celebrity theorist Marshall McLu-han who is known for saying that the ‘medium is the message’ (McLuhan 2001). McLuhan also said that advertising was the art of the twentieth century (McLuhan in Campaign US, 2015). I do think that when art directors design a print advertisement, they are applying the same types of rules, tools and techniques that artists do when creating their works, such as a painting, and also paintings are messages. The filmed interviews that HAT does with advertising legends such as yourself are excellent examples for young people to look towards for leadership. It is great what you were saying about advertising, how you were reflecting things in society. You weren’t taught rules to create advertising, so you just reacted viscerally to solve a client’s marketing or communication problems.

Trott: What I did at my agencies, well at the first and best of my agencies. First, we looked at what everybody else was doing, and did the opposite. What they were doing was hiring the most expensive and stylish talent, and the most expensive talent in terms of creative staff. What my agencies did was hire rebels and rejects.

Kids who couldn’t get a job anywhere else, they were very working class and they were very rough. Then I said if you shut up, I’ll train you and ‘soon you’ll be earning more than those other guys.’ And they did. Street smarts cuts through all of that academic learning, because they think ‘Right how do I survive here? How do I make sure that guy doesn’t have me over? How can I think of something that he hasn’t thought of? What can I do what somebody else wouldn’t have done? How can I get through the day without being beaten up?’ When you grow up on the wrong side of town, you’ve grown up using your brain from day one. Vs. people who were lucky enough to go to university and pass all of their exams, get good marks and learn to get approval from the teacher, it’s a different mind-set. People like that are not used to me. I want the other kids. I want the kids that are constantly think-ing that they’ve only got a tenth of the money the other guys got, and they want to beat them.

When we had these kids that nobody else would touch as part of my creative staff in my London agencies we got voted in a 10-year period, the best agency in London, and Adweek magazine in New York said we were the most creative agency in the world. That’s with kids that were rejects from every other agency.I started a thing in the mid [19]70s with D&AD (Design and Art Direction) the organisation that awards the best in creativity and is based in London. I didn’t like the way kids were being taught over here in the UK. So, I decided to teach them the way I was taught in 1969 at Pratt in New York. At Pratt they said we can teach you graphics, typography, colour, film, anima-tion everything, but the only thing we can’t teach you is advertising. We don’t know anything about it. So, we will send you to Manhattan so that you can be taught by the professionals. One day a week we would go to Manhattan and be taught by the guys on Madison Avenue. Not by teachers, but by professionals. It was like being in boot camp. We learned so much that after a year or two I came back to London and I was five years ahead of everybody else. So I said to D&AD let’s start this training scheme, where I’ll take these kids, but we won’t do it the normal English way, where you only take the best students, and the best portfolios, what we will do is take motorcycle messengers, secretaries, everybody who can’t do it, but wants to do it, and what we will do is if we see progress then we’ll keep them in the course, and if not then we will kick them off. So, it is all about how hard you work, and not about how talented you are. So, I said to D&AD we will make the cost £5 a course if you’ve got a job, and £2:50 if you don’t have a job. After about five years it was so popular there were four classes running every Wednesday around London. At all the different agencies, and D&AD said we’ve got so many classes that we’ve got too many people applying. What we are going to do is only take the best people for the course. Well that was the exact opposite of what I wanted it to be. It was getting elitist. So, I said well I’ve got my own agency now, just give me the names of all the rejects and I’ll take them. They gave me 40 names. Then I said to the kids, ‘you are rejects and the D&AD said you are not good enough to work in advertising. If you sit down and shut up and do what I say…’

Carl: Oh my god there’s an earthquake (Figure 6).

Trott: I didn’t know you had earthquakes in Mexico?

Carl: Yes. I’ll be right back.

Figure 6: Earthquake via Zoom. (10:34 am CST June 23. Temblor was 7.5).

Trott: (a few minutes after quake has finished, the interview continues) … you will get more jobs than the people in the main course.’ And it was true, and we did. All those kids that came to our place got jobs, and half the kids in the D&AD course didn’t get jobs. The people who were regarded as the best were not as good as the rebels and rejects. The proof of it was that the next year, we had people pretending to be rejects actually being accepted for the main course.

Now two years after that. I kept the course going for 10 or 15 years. Twenty years after that I was at D&AD getting a lifetime achievement award and there were 15 people coming up to my table to shake my hand, and they were all now creative directors at really good agencies in London who had been on that reject course, because D&AD had said that they were not good enough to be in advertising. It’s nothing to do with the traditional ways, it’s all about energy. All I ever did was find the people who were hungry enough. If you find the men and women who are hungry enough it is very easy for me to turn them into gold.

Carl: I have two more questions to ask you please. I wanted to ask about the class system in advertising. When I would visit the UK to go to business meetings, I would notice that the advertising business seemed to be very class-based, with the account people being ‘posher’ than the creatives.

Trott: Yes, creatives tended to be more working class, and account people tend to be more middle class. That is because the clients would be more middle class. And account people would deal with clients. But the creatives, since you’ve got to come up with lots of ideas, then that’s where the working-class people go. But you wouldn’t put working class people with cli-ents as the client wouldn’t have much confidence in them. It’s always been the same stereo-type; many people think that the working-class accent means you’re pretty stupid, and you’ve never had a good education, don’t know what you’re talking about and can’t be trusted. That was the working-class image in the UK. So, you don’t put that in front of the client, you want a middle-class image which is where you’re calm, and been to university. You are educated, smart and clever, and that’s what the clients want to see. People like them.

Carl: That was your experience in the UK, did that happen in America in the 1960s and 70s?

Trott: No. In America not really. But what I noticed in America was that the Italians and the Jewish people ended up in the creative department and the WASPs (White Angle Saxon Prot-estants) ended up working directly with the client. Because the clients were WASPs. But in the USA the clients wanted access to the creatives; in England the clients didn’t hardly ever meet the creatives. The account guy is the one that builds the relationship with the client. The client trusts him. The client accepts what he says. The client trusts the account guy, and might even buy work they may not like just because they trust the account guy. In the UK creatives don’t want to see clients anyway. If the agency has a good account person then they can sell the crea-tive work, a lot better than the creative person can. Vs. in America and Canada, the creatives want to fight more, thinking ‘I want to sell my work. I can sell my work better than anybody.’

Carl: There have been quite a few TV shows and movies about the advertising industry and what it is like to work in it. There was one really bad movie with Mel Gibson called What Women Want where Gibson is an ad exec in an agency. I think it did not accurately represent how the advertis-ing business is at all. Do you know the cable TV show Madmen which reflects the advertising world on Madison Avenue in the 1960s and 70s? As you said that you had been working on Madi-son Avenue as a student in what the Americans call the beginning of the golden age of advertising in the late 1960s. Does the show Madmen reflect accurately that world you experienced?

Trott: Well Madison Avenue was split down the middle. With the famous British ad man David Ogilvy on one side, and the American Bill Bernbach on the other. Bill Bernbach was the modern, counter-culture, anti-establishment man. Everyone who went to art school went to work with Bill Bernbach. The other people were working at the bad agencies on the other side. The ones drinking whisky in the middle of the day, smoking cigarettes and getting laid all the time, wearing suits and having slicked back hair. It was about money. Their advertising was rubbish. They were the WASPy advertising side of it. Whereas the Bill Bernbach side of it was the side that was all hippies, and people who loved advertising and were the complete opposite of the other side of Madison Avenue. People like Mary Wells Lawrence, who showed real people in their ads, ordinary people. These were ads that people loved. You didn’t see any of that side of Madison Avenue on the TV show Madmen. Madmen was about the Ogilvy side of the street.

Carl: Well thank you Dave, this is the end of the interview. Are there any other thoughts you have on ‘Advertising for the Human Good’?

Trott: By the time a client gets to ask an ad agency to do some work for them they should have considered whether it is for the human good, long before they get anywhere near to asking for an advertising campaign to be created.

Advertising is just the delivery system. Advertising is a tool. It depends on what you use it for. Advertising for a good purpose, is like saying money for a good purpose. It can be used for good or bad.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Campaign US. (2015). History of advertising: No 153: Marshall McLuhan’s global village, 5 November. Available at https://www.campaignlive.com/article/history-advertising-no-

153-marshall-mcluhans-global-village/1371219 (last accessed 11 July 2020).

History of Advertising Trust. (2018). Inspiring minds: In conversation with British adver-

tising legends: Dave Trott. Available at: https://www.hatads.org.uk/learning/inspiring-minds/inspiring-minds-Dave-Trott.aspx (last accessed 10 July 2020).

McLuhan, M. (2001 [1964]). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. London: Routledge. Statista. (2019). Advertising in the United Kingdom — Statistics and Facts. Available at:https://www.statista.com/topics/1747/advertising-in-the-united-kingdom (last accessed 11 July 2020).

Trott, D. (2009). Creative Mischief. London: Loaf Marketing.

Trott, D. (2013). Predatory Thinking: A Masterclass in Out-thinking the Competition. London:

Macmillan.

Trott, D. (2015). One + One = Three: A Masterclass in Creative Thinking. London: Pan. Trott, D. (2018). Everyone else is doing it. Dave Trott’s blog. Available at: https://davetrott.

co.uk/2018/02/everyone-else-is-doing-it (last accessed 11 July 2020).

Trott, D. (2019). Creative Blindness and How to Cure It. Petersfield: Harriman House.

Trott, D. (2020). Toilet. Dave Trott. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ieu0H7cj9p0&list=PL190MFFr5cyoVDdCq5zKJE1ewKozv7neI (last accessed 11 July 2020).

How to cite this article: Jones, C. W. (2020). The World According to Dave Trott: An Interview. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 15(2), 151–161. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.393

Submitted: 13 July 2020 Accepted: 13 July 2020 Published: 31 July 2020

Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Image: Courtesy of Dave Trott