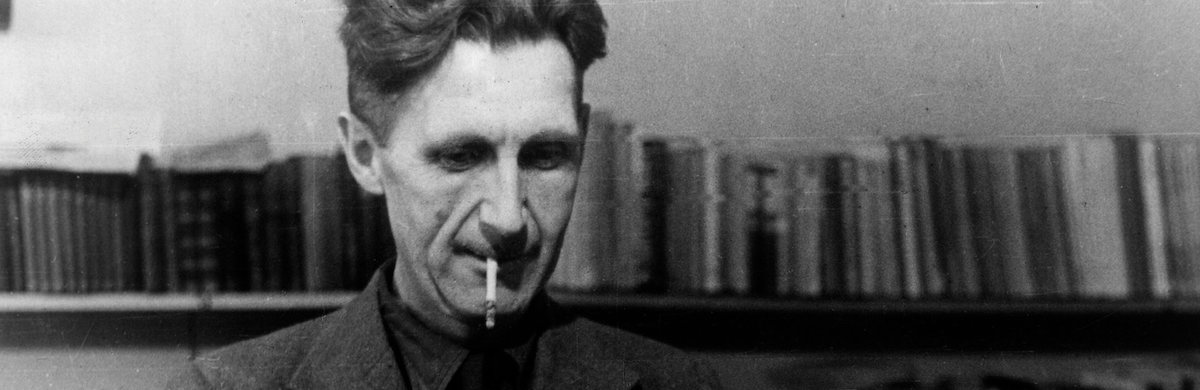

Reading George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four again, now, hurts. And I’m not the only one to be revisiting it: sales of the book have soared in the past week. What you had previously thought you read at a cool, intellectual distance (a great book about “over there”, somewhere in the past or future) now feels intimate, bitter and shocking. Orwell is writing of now when he writes, “Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller.”

Of course, we all have to keep our heads (especially we have to keep our heads). The lies about the crowd size at Donald Trump’s inauguration by the hapless White House spokesman Sean Spicer at his first briefing were not earth-shattering. But any lie from this podium is deeply unsettling. Any hopes that Trump or his team were, underneath it all, “normal” rightwingers, have dissipated.

The post-truth era certainly shares aspects of the dystopian world of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Michael Gove’s infamous comment that Britain has had enough of experts is just one step away from 2+2 = 5. In the interrogation scene in 1984 this is the most appalling moment: before now we read it as a ludicrous indictment of the rejection of reality (surely, we conclude, the party itself must know that 2+2 = 4; science, machines all depend on it). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the elite, personified by O’Brien, foster and control this willingness to believe one thing one day, and one thing another. Now, it seems, the party itself may believe the lie. As Orwell writes: “Science, in the old sense, had almost ceased to exist. In Newspeak there is no word for science.”

Then there is privacy – Orwell puts the diary and the private self at the heart of his writing. In 1984, keeping a diary is Winston’s first act of transgression. Orwell knew that authoritarian regimes want the heart and soul of people. His two-way telescreens predict social media. And we have, perhaps unwittingly, wandered into a world where feelings have never been more easily swayed: Trump summons them up personally and directly. In the book, Winston is suddenly struck that his mother’s death, “had been tragic and sorrowful in a way that was no longer possible … She had sacrificed herself to a conception of loyalty that was private and unalterable.” It could no longer happen because “there were fear, hatred and pain but no dignity of emotion, no deep or complex sorrows”.

But this new world has been a while coming. Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway’s “alternative facts” were foreshadowed by the George W Bush adviser who said in 2002 that the new American empire was “creating [its] own reality”. As in the 1930s, war has been at the heart of the corrosion of trust in politicians. The lies over Iraq and the quagmire of Afghanistan were followed by the financial crash of 2008, and bankers’ bonuses – making people far more willing to disbelieve the remote metropolitan media and be drawn to the false dawn promised by Trump.

Yet these are the obvious big lies. There has been a long drift away from rational beliefs that we have watched too passively. Mistrust in facts was sown by the insistence on creationism and climate change denial by politicians and in many US churches. But it’s not just America – in India, government officials say that cows don’t contribute to global warming because they breathe out oxygen. Even universities with their “no platforms” have added yeast to the brew.

Trump is not O’Brien. He is more like a cut-price version of Big Brother himself. Instead of the elite of Nineteen Eighty-Four, who keep Big Brother’s identity a mystery while they keep total control, this Big Brother, with his direct Twitter relationship with his followers, is fully on show. And as Orwell foresaw, his slogan could be “Ignorance is strength”.

.