Big politics is big data. That is at least what we are today often led to believe. A study estimates that in the third US presidential election debate, political bots posted 36.1% of the pro-Trump tweets and 23.5% of the pro-Clinton tweets. With 15 million respectively 11 million followers on Twitter, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton reached significantly sized online audiences in their campaigns. Big data was in the US presidential election also used for targeted campaigning and predicting the result.

The Failures of Big Data Politics

The tech pundits pronounced that big data was the factor determining election results. Wired Magazine wrote that the “marriage of big data, social data will determine the next President” and summarised this claim in a simple formula: “Big Data + Social Data = Your Next President”. Eric Siegel, founder of Predictive Analytics World and Text Analytics World, wrote in a Scientific American blog post that science “is playing an important role for mass voter persuasion in the U.S. presidential race. It’s a numbers game: Predictive analytics targets campaign activities, strengthening a campaign’s army of volunteers by driving its activities more optimally”. News organisation Firstpost argued that “technology could play a major role, particularly Big Data, in deciding who gets to wear the crown eventually. While Trump has berated the technology, calling it ‘overrated’, the Hillary camp has gone all out to mine and collect data from every possible source: from voter registration and public records to social media activity”. Adriana Coppola, a planner at the marketing and consulting company SapientNitro, wrote in the Guardian that “big data will win future elections”.

Numerous observers argued that the Trump campaign cared much less about big data than the Clinton campaign. So for example, Data Insider reported, “Word on the street has it that the Trump campaign has taken a traditional approach to campaigning, getting their message out via social media, TV and radio advertisements, email campaigns, and good old grassroots ‘boots on the ground’ strategies, like town hall meetings and signs in front yards. The Clinton campaign has relied more heavily on big data”.

Politico Magazine reported on the Clinton campaign’s strategic advantages obtained by an algorithm, based on which Elan Kriegel, the campaign’s director of analytics, determined how and where money was spent: “Now, with Donald Trump investing virtually nothing in data analytics during the primary and little since, Kriegel’s work isn’t just powering Clinton’s campaign, it is providing her a crucial tactical advantage in the campaign’s final stretch”. The Washington Post wrote about how the Clinton campaign used the Ada algorithm: The “algorithm was said to play a role in virtually every strategic decision Clinton aides made, including where and when to deploy the candidate and her battalion of surrogates and where to air television ads – as well as when it was safe to stay dark”.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Trump was a data Luddite and therefore at a strategic disadvantage: “Among Donald Trump’s unorthodoxies is his campaign’s refusal to use big data. ‘I’ve always felt it was overrated,’ Mr. Trump said in May. ‘Obama got the votes much more so than his data-processing machine. And I think the same is true with me’. […] Campaign professionals in both parties agree the Democrats have a large lead in information about voters – and that smart use of data can make the difference, at least in close elections”. According to the commentariat’s assessment, big data should have brought a big win for Clinton. Big loss and big disappointment, however, turned out to be the true realities in the US presidential election’s big data politics.

Other sources (AdAge, NBC) indicated that Trump got late into big data campaigning, paying significant sums to data firm L2, data campaigning firm NationBuilder, and the British data science company Cambridge Analytica. Channel 4 reported that both the Clinton and the Trump campaign used big-data based voter targeting and held digital files on all voters with data from sources such as purchase histories, television watching, credit card spending, magazine subscriptions, donations, memberships, etc. as well as data obtained from conversations with voters at their doorsteps. One Trump campaigner commented on the conversation with a voter: “As we were talking, I was flipping through the different tabs in the app, and dropping in everything I could find: Christian, special needs, social needs, child, child care”.

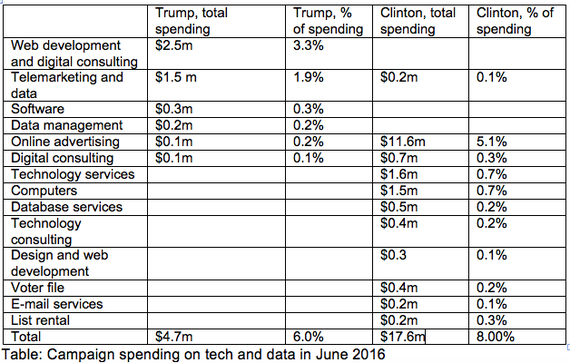

So it is probably fair to say that both campaigns invested in big data analytics. There are, however, indications that the Clinton campaign’s data spending was much higher. Data show that in October, the Clinton campaign had raised US$ 1.3 billion, the Trump campaign just US$ 795 million. The table below shows data provided by Bloomberg for both campaigns’ spending on tech and data in June 2016. According to this source, the Clinton campaign not just invested a higher share of its budget on data and tech than the Trump campaign, but it spent 3.7 times what the Trump campaign invested.

What all of this tells us is that big data does not win and cannot predict elections. It is a techno-fetishistic myth to believe that the more money a campaign invests into data analytics, the larger the likelihood of electoral success. It is the complex combination of structural conditions, economic and political contradictions, crises, political subjectivities, political structures of feeling, ideological factors, organising, campaigning and communication that determines election results. Data, algorithms and tech form just one of many relevant factors. Algorithms are not just deterministic and cannot understand emotions and morality, they also can make false predictions because real society and real subjectivities are much more complex and unpredictable than all the calculations that big-data algorithms perform. Big-data based algorithms may have told the Clinton campaign that states like Wisconsin are an easy win and that she therefore does not need to visit them. In the end, Trump won such states.

It is a general development not limited to the USA that decades of right-wing politics focusing on fostering precarious labour, wage stagnation at the expense of rising corporate profits, heavy exploitation, de-industrialisation, the indebting of everyday people, cuts of social security, privatisation and deregulation have resulted in large inequalities. The consequences are anger as well as feelings of alienation and being disrespected among significant parts of the population. Inequality and anger combined with right-wing populism that scapegoats minorities, immigrants, refugees and people of colour and an impoverished public sphere, in which almost all mainstream media focus on tabloidisation, acceleration and spectacles, is a highly dangerous amalgamation. It is an absolute irony that it is the American billionaire Donald Trump, one of the system’s economic beneficiaries, whom a significant share of the American white working class see as their saviour. Promises of salvation, however, often turn out to be false promises. In the US election, Bernie Sanders’ politics of democratic socialism as Trump’s contender may have resulted in a different result. Clinton’s big data politics was a much weaker opponent for Trump’s right wing populism than democratic socialism. History tells us that whenever and wherever the political left is weak, the far-right tends to be more successful. The 2016 US election is not different from this trend.

The Failures of Big Data Polling

Polls of polls are another big data instrument that has become a popular tool for trying to predict election results. And also the big data pollsters got it wrong. On November 8, the New York Times predicted that Clinton had a 85% chance of winning and its poll of polls forecast 45.9% for Clinton and 42.8% for Trump. Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight predicted in its polling aggregation on November 8 that Clinton had a 71.8% chance of winning, Trump one of just 28.2%. Silver argued after the election that FiveThirtyEight provided the analysis that was least wrong, saying that “FiveThirtyEight gave Trump a better chance than almost anyone else”. But when you are wrong, then it often does not so much matter that somebody else made even more ridiculous claims. You are still wrong. The point is that big data analytics seems to be simply ill suited for predicting the development of the world. In fact, it might not at all be possible to predict the future of a complex, dynamic system.

To be fair, one must say that Silver is aware of some of the limits of polling: Nate Silver admits: “But people mistake having a large volume of polling data for eliminating uncertainty. […] Pollsters simply can’t do much about voters who make up their minds only after the survey is completed”. Society’s complexity is much higher than any algorithm can manage. Society has a dialectical complexity that cannot be quantified and can only be understood qualitatively in terms of social struggles, contradictions, ideologies, political power, and issues relating to (in)equality, (in)justice, (un)fairness, exploitation, and domination.

It can very well be that disenfranchised and angry voters, who are susceptible to demagogues’ simplistic messages that scapegoat minorities as being the causes of capitalism’s social problems, simply do not talk to pollsters or lie to them because they are afraid or distrustful, feel ashamed or see the pollsters as part of the phenomenon they oppose. Pollsters also wrongly predicted the Brexit referendum’s result. This fact should make us question the naïve belief in the power of quantification, mathematics, computing, statistics and big data. Society’s development is not decided by algorithms, but by power struggles and power dynamics. Big data politics tends to displace energy, time, resources and space from the complex task of making and organising arguments and campaigns that present convincing alternatives. Lost in the depth of data and quantification, neoliberalism loses ground to right wing extremisms’ emotionally laden populism. Many then find the qualitative emotionality of the prejudice and the stereotype more appealing than the argument and tweet that an algorithm predicts to be the most likely candidate for winning over the largest number of people. Given that the world is not a machine, treating it like a machine will often have negative unintended consequences.

The Failures of Big Data Capitalism

Neoliberal capitalism created a monster that is based on the logic of constant quantitative increase of profits, profit rates, shareholder values, bonuses, and key performance indicators. It is based on the logic of not just commodifying, but also measuring and ranking everything. The emergence of big data stands in the context of neoliberalism’s fetishism of quantification. Neoliberalism is big data capitalism, a capitalism that in an ever-expanding number of realms of society puts the logic of quantification and commodification over people. Big data is part of the monster that was unleashed a long time ago and that has lashed about without restraint since decades. The Apprentice‘s ruthless and fierce celebration of possessive individualism, competition, entrepreneurship, managerialism and neo-liberalism gives an impression of Donald Trump’s ideal model of society. It is a society that does not challenge, but deepen the dominant model.

The capitalist fetishism of quantification has as its negative downside an increase of inequality, precarious labour, a drop of the wage-share, increasing debt levels of everyday people, low-levels of corporate taxation and as a consequence a fiscal and austerity crisis of the state, etc. Inequality and disrespect breed anger that can easily be channelled into barbarism as a political project. Neoliberalism is experiencing its own negative dialectic. We not just can learn from the US elections that the logic of big data is mistaken and should be replaced. We can also learn that the very logic of quantification raised to a model dominating society is a failed political project. There might still be a slim chance to overcome this project and replace it by one that is oriented on commonality and humanity.

Images:

By Donald Trump August 19, 2015 (cropped).jpg: BU Rob13 Hillary Clinton by Gage Skidmore 2.jpg: Gage [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

By Thierry Gregorius (Cartoon: Big Data) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

By 2ndAmendment (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Darren Halstead on Unsplash