Lawrence Jackson/Made with Canva, CC BY

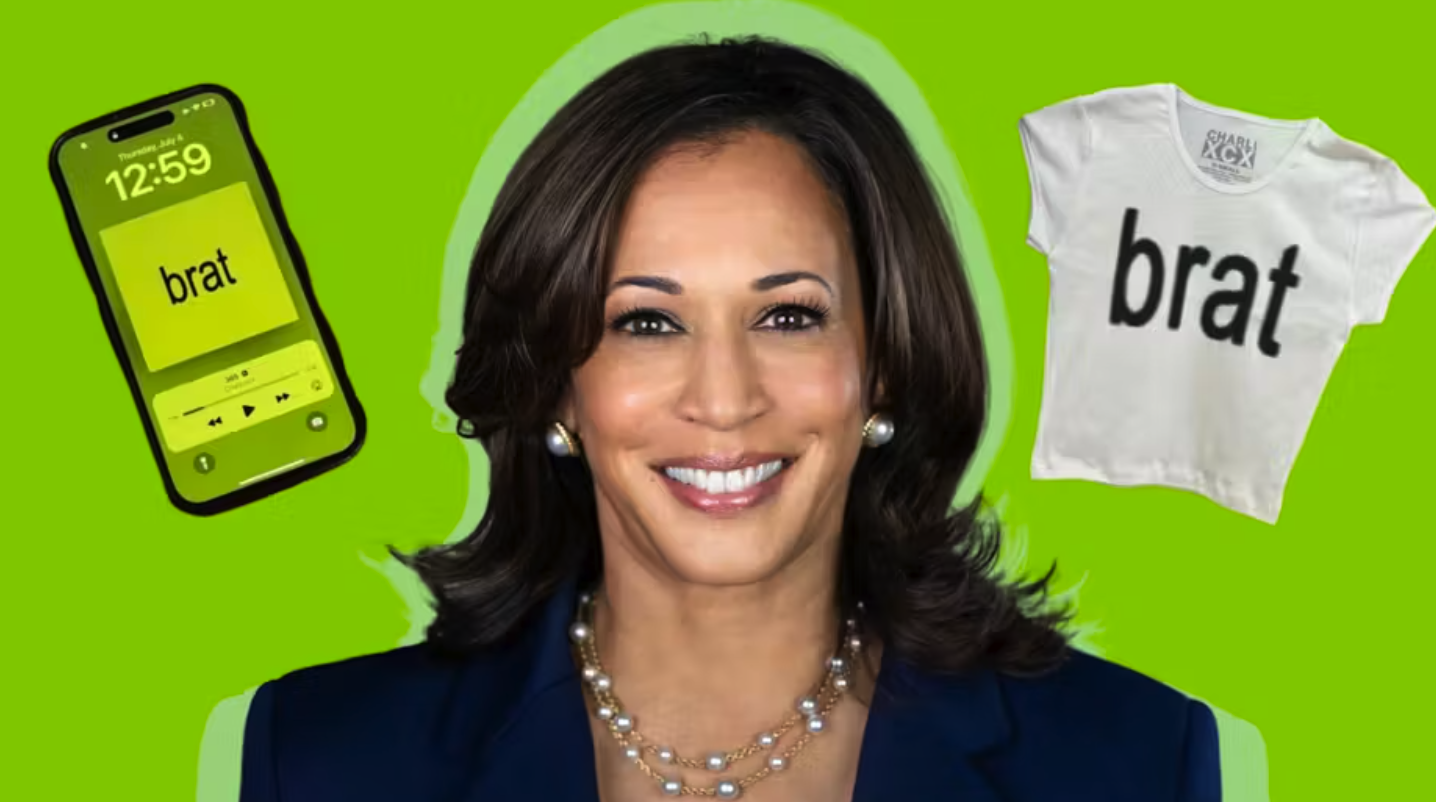

When Kamala Harris was confirmed as the new Democratic party nominee, a host of celebrities rushed to endorse her – but one has had significantly more attention than the others. Singer Charli XCX endorsed Harris in her signature minimalist way by posting “kamala IS brat” on X.

The post went viral almost instantly, with millions of views, and Harris’s own X account switching its colours to neon chartreuse – the shade of the album cover for Charli’s new album, Brat.

The internet thrives on novelty and inside jokes. That’s partly why memes – a fairly middle-aged phenomenon that first originated in the 1990s – are still going strong, while we’ve long seen the back of Bebo, Vine and Clubhouse (what are those, you ask? My point exactly).

The popularity of memes means they have become an important vehicle for political communication. In my research, I have identified four roles of memes: political mindbombs, fast-food media, everyday slang and a soothing device. Charli XCX’s endorsement of Kamala Harris is a perfect “political mindbomb”.

No one’s 20s and 30s look the same. You might be saving for a mortgage or just struggling to pay rent. You could be swiping dating apps, or trying to understand childcare. No matter your current challenges, our Quarter Life series has articles to share in the group chat, or just to remind you that you’re not alone.

Read more from Quarter Life:

- How to resolve friendship tension like Lorde and Charli XCX

- Five outdoor summer activities from British folklore to try with your friends

- What young neurodivergent employees need to know about starting work — and how to get the right support

The term “political mindbomb” was coined by the co-founder of Greenpeace Bob Hunter, who claimed that a powerful visual message can cut through the noise and affect the minds of people – not immediately, but in the long run. He used the example of a photo of a bleeding whale trying to escape a hunting ship. He sent the heartbreaking picture to media outlets to affect the minds and feelings of readers all over the world, and hopefully encourage them one day to vote or protest against whaling.

When Kamala Harris was announced as “brat”, the suit-wearing, experienced and sharp vice-president received a gift of vibes, rather than something concrete. Charli XCX posting a serious paragraph on why Harris is suited for the top job in the country would not have created the same effect of viral potency.

The three words, written by a 31-year-old British pop singer, are cryptic for some internet users. You need to have been following the emerging coverage of Charli’s album and the subsequently coveted brat aesthetic in the likes of Vogue this July to understand what exactly is being talking about. But as with any good meme, “brat” is defined by incompleteness.

When I explain memes to my students, I often use the metaphor of a half-baked joke. A good meme requires the reader to complete the sentence and make sense of why the concoction of an image with over-imposed text, for example, is supposed to be funny, irreverent or sarcastic. You need to know some context, some popular culture, some internet or lifestyle slang. A good meme is not for everyone, and this closed-community feel makes them precious.

Dupe/Emily Patnaude, CC BY

Linking one of the most influential women in the US today with “that girl who is a little messy and likes to party and maybe says some dumb things some times”, as Charli XCX defines “brat”, is a bold move that seeks to inject fun and relatability into Harris’ public persona.

Harris’s team may be embracing memes because of the complicated effects of memes and viral culture on political candidates in the past.

In 2016, the treatment of memes by the Democrats could be called heavy handed. Many now associate the “Pepe the Frog” meme – a laid-back green cartoon frog known for the speech bubble “feels good man” – with right-wing nationalism. But it started off as a humble meme about social awkwardness before rising to prominence when Hillary Clinton’s office released a post aligning Pepe the Frog with the alt-right movement, cementing its cultural position.

In another instance, Labour politician Ed Miliband’s awkward eating of a bacon sarnie, generally associated with working-class cafes, generated a whirlpool of memes that questioned his relatability to the general public, and may have cost him the UK elections.

A word of caution, though: memes are always subversive, they cannot communicate complex and progressive ideas with consistency. Their very nature of sarcasm, irony and jester-like playfulness makes them a dangerous tool for a politician. They can quickly be turned against a person who thought memes would work in their favour. Having said that, riding a bit of a viral wave of awe and surprise, and exploring the hidden playfulness of a serious political candidate, does feel rather “brat” – however you decode it.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Anastasia Denisova, Senior Lecturer in Journalism, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.