This paper starts from the premise that research into how producers negotiate issues of diversity and multicultural content in Europe is rare and mostly relies on interviews and documents, and furthermore work on understanding those negotiation processes in relation to children’s screen content is even rarer. The article seeks to reflect critically on an alternative hybrid research method, which aims to open up a space for dialogue about production processes and was applied in three workshops about children’s content and forced migration that the authors ran with content creators and broadcasters of children’s screen content in 2017–2018.

TV production studies face a methodological challenge which arises primarily from the teamwork nature of screen media production. This is because research needs to probe not only into individual decision-making or organisational constraints, but a whole web of interactions among creatives and their workplace communities and contexts. Scholars in the field acknowledge the challenge by seeking to study ‘production culture/s’ (Banks et al., 2016: x; Caldwell, 2008) and stressing that media industries and practitioners are subject to an increasingly complex array of larger ‘socio-political forces and more local cultural manifestations’ (Freeman, 2016: 67). The range of methods at their disposal for studying this interactive production process usually consists of interviews, ethnographic observation and scrutiny of documents such as publicity materials, company data and items in the trade press. Yet interviews and observations come with pitfalls as well as advantages. In recent years some of the pitfalls, discussed below, have been explored collectively, including at a University of Leeds conference on ‘Advancing Media Production Research’ in June 2013 and in material generated at the launch of the University of Nottingham’s Institute for Screen Industries Research (ISIR) (Freeman, 2016).

For academic researchers, the task of developing trust and obtaining access looms large in any method involving personal contact with industry practitioners. As Amanda Lotz argued in a post on the original ISIR website, the nature of industry jobs, marked by ‘day-to-day deadlines and extinguishing immediate fires’, makes it hard for executives to find time for thinking at the ‘broad level available to academics’, which makes conversations difficult (Lotz, n.d.). Those difficulties can work both ways. Surveys show that industry practitioners who work in academia cannot expect a uniformly positive reception from non-practitioner colleagues (Mateer, 2019: 14). One survey respondent attributed this state of affairs to industry and the academy being ‘two separate worlds with two separate languages and ways of understanding’ (quoted in Mateer, 2019: 21).

In light of communication obstacles and industry complexities, there is good reason, as Lotz notes, to use aspects related to media industry operations as a ‘lens for trying to make sense’ (n.d.) of a particular phenomenon, rather than those operations themselves serving as the object of study. The phenomenon at the centre of research referred to in this article was the level of diversity and multicultural representation in children’s screen media in Europe in the context of a surge in forced migration into Europe in 2015–2016. Our present contribution itself, however, addresses the methodological challenge of gaining insights into, and understanding of, the negotiation of regulatory, commissioning and production processes behind what made it to screen in this period. It starts from the premise that research on such negotiation processes has been rare even in the context of diverse and multicultural adult programming and has mostly relied on interviews and documents (see, for example Dhoest, 2014: 107; Leurdijk, 2006: 26). For children’s programming it has been even rarer (Steemers, 2016: 126) and has again been conducted mostly through interviews with some participant observation (see, for example Buckingham et al., 1999: 147–174; Steemers, 2010: vii).

Yet negotiation over production for children is often too sensitive, because of commercial constraints and a lack of their participation (Sakr and Steemers, 2019: 114–120, 127–131), to be made transparent through interviews or even observation. Neither method can be relied upon to overcome the reticence instilled by industry hierarchies or expose what really takes place during the narrow pre-production window when key production parameters are determined. The aim of the article is to reflect critically on an alternative hybrid method – one consisting of an extended group interview using screen content to stimulate reflection – applied in three workshops that the authors ran with producers and commissioning editors of children’s screen content in 2017–2018. The paper starts by exploring arguments for a fundamentally multi-method approach to production studies.

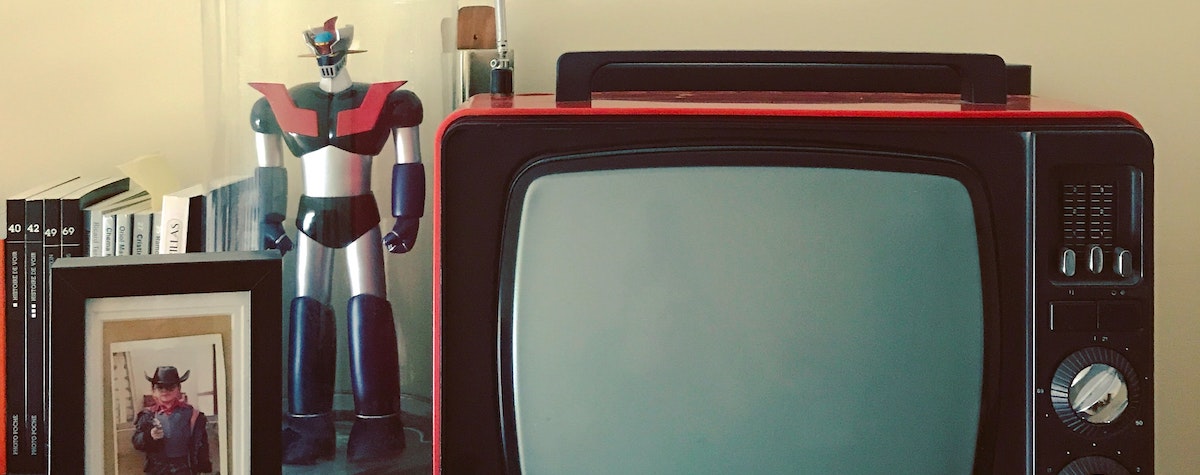

Photo by Alberto Contreras on Unsplash