After four years of tunnelling and building, London’s Underground network was extended to reach two new stations on 20th September 2021. With an estimated cost of £1.1bn, the Northern Line has grown by 1.8 miles to connect Kennington in South London with Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station. Around £270m towards the costs of building the new line, which serves the housing and retail developments located along Battersea Riverside, was contributed by companies developing the area. This bought the developers considerable influence on decisions that have since had an impact on mapmaking and social equality alike.

For their money, the developers wanted a few things in return. The first of these was to situate the two new stations within the Zone 1 ticketing area of the London transport network. Homes and businesses inside this central area are often more prestigious and can fetch a higher price than those within other zones. However, the geographical locations of Nine Elms and Battersea Power Station sit firmly inside what has traditionally been Zone 2.

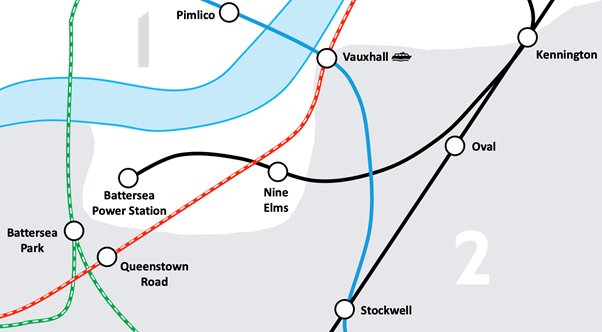

The location of the new stations, showing how Zone 1 would have to be shaped to include them. Kennington show in its new position straddling two zones (Image: Authors’ own)

No problem – simply extend Zone 1 a little bit below the River Thames. A minor amendment, it would seem, with barely any ramifications. Yet, for the designers of the iconic Tube map, the decision to allow the new stations to be part of Zone 1 caused an uproar, risking the integrity of one of the most successful cartographic designs ever produced. The iconic Tube map, which was devised by Henry Beck in 1931 and eventually published in 1933, is world-renowned for its schematic layout and ease of use. Its straight lines and 45- and 90-degree angles revolutionised transit map design and led to countless imitations around the globe, for mapping underground railways and just about anything else. One of the reasons for its enduring success is the versatility of the map’s design – it has accommodated the many changes associated with the growth of London’s Underground network for 90 years – and is still used by millions daily.

The drawing of the Northern Line Extension, however, appears to have pushed the famous design beyond its limits. Firstly, Kennington Station, which has always been located inside Zone 2, had to be moved to become a dual (Zone 1/2) station that straddles both zones. This allowed the map to continue to show ticketing zones as concentric rings (as it always has done). With both Vauxhall and Kennington now dual-zone stations, the issue would appear to be solved. In keeping with the design principles of the map, however, the line from Battersea Power Station to Kennington (both classed as Zone 1 for that trip) should not pass through Zone 2. Likewise, the line from Queenstown Road to Vauxhall (both classed as Zone 2 for that journey) should not pass through Zone 1.

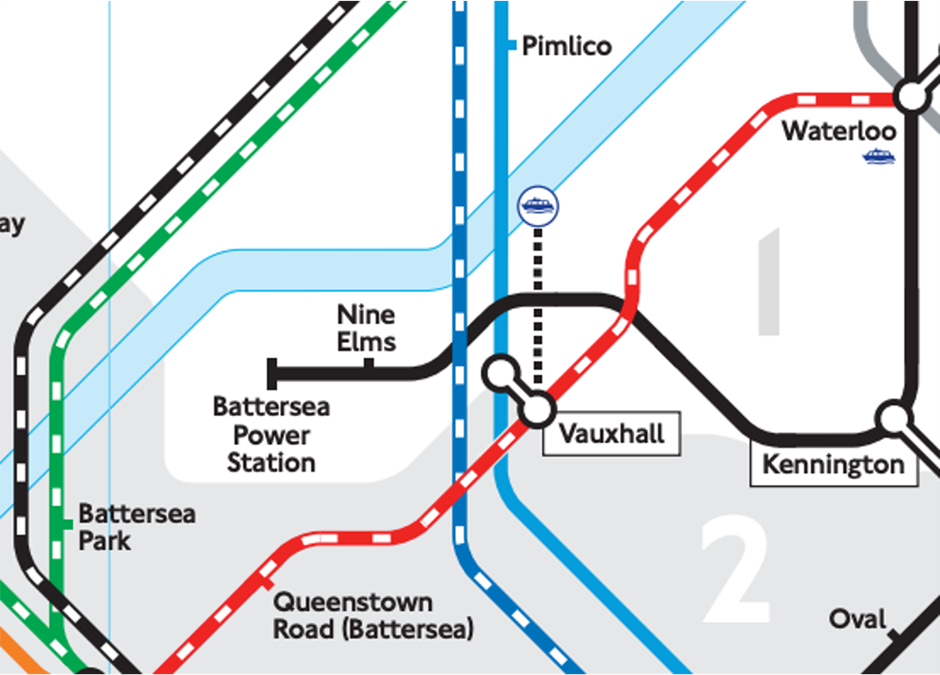

How the 2021 tube map represents the new zoning (Image: TfL)

Beck’s approach to the problem of mapping the Underground was to promote topology over topography. He realised that by showing how stations were connected at the expense of retaining their strict geographical locations was far more useful. The removal of street-level detail by MacDonald Gill in his calligraphically exuberant design of 1920 had paved the way for Beck’s radical rethinking of the structure of the map. In turn, Beck’s geometrically regular design resonated with the public, who recognised its connotations of order and efficiency that coincided with their image of everything that a modern transport system should offer.

In applying Beck’s liberal approach to geography by moving Vauxhall Station south of the Northern Line and by inserting several fictitious turns in the track, the zoning can be made correct. This has seen the inclusion of a rather long dotted line to show its riverboat connection, however, despite Vauxhall Station now being shown some way from the river.

Although its mapmakers have overcome the Tube map’s latest design challenge, in this small corner they have also illustrated how social inequality can be manufactured and reinforced through mapping. The Northern Line Extension was funded by a £1bn loan to the Greater London Authority, which will be paid back by the developers of the surrounding area and topped up by money collected from business rates. So, if the developers are paying a large share of the costs for the line, why shouldn’t they be allowed to dictate the zoning? This would seem fair, except that the developers balked at their required contribution of £266.4 million to the Northern Line Extension – a project that would significantly increase the value of their development – and lobbied Wandsworth London Borough Council to allow them to reduce the provision of social housing from the usual share of 33% to just 9%.

Battersea Riverside now has its own Underground line, very little social housing, and has been placed squarely within Zone 1 by Transport for London (TFL). What more could the developers have asked for? Through their elegant solution to zoning, the Tube map’s cartographers have managed to conceal the politics behind these decisions, making this new area appear as if it has always belonged in Zone 1. In doing so, they have pushed up the profits of the developers who managed to avoid having to build more affordable housing.

Although not responsible for generating the circumstances that allowed the developers to lobby the Council, the Tube map has still managed to legitimise the outcomes. Like any map, its aesthetics conceals its politics.

Read more about the design history of the Tube map in The Cartographic Journal, the peer-reviewed journal of the British Cartographic Society.

Photo by Call Me Fred on Unsplash

About the authors: Doug Specht is a Chartered Geographer and the Director for Teaching and Learning within the School of Media and Communication at the University of Westminster. His research examines how knowledge is constructed and codified through digital and cartographic artefacts, focusing on development issues in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Alexander J. Kent is Reader in Cartography and Geographic Information Science at Canterbury Christ Church University in the UK, where he lectures on map design, GIS, remote sensing and on European and political geography. His research explores the relationship between maps and society, particularly the intercultural aspects of topographic map design and the aesthetics of cartography. He is also Chair of the ICA Commission on Topographic Mapping and formerly President of the British Cartographic Society.

Suggested further reading

Kent, A.J. (2021) When Topology Trumped Topography: Celebrating 90 Years of Beck’s Underground Map, The Cartographic Journal 10.1080/00087041.2021.1953765

Hochstenbach, C, Musterd, S. (2021) A regional geography of gentrification, displacement, and the suburbanisation of poverty: Towards an extended research agenda. Area. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12708

Scheurer, J., Curtis, C., & McLeod, S. (2017) Spatial accessibility of public transport in Australian cities: Does it relieve or entrench social and economic inequality? Journal of Transport and Land Use. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26211762