Austria is a small country in the heart of Europe with about 8.7 million inhabitants. In international news coverage, you can normally not find much about Austria. But this small country has made it repeatedly as a headline into world news with events that document the strengthening of the far-right in politics: In 1986, Kurt Waldheim, a former member of the Nazis’ Sturmabteilung (SA), became Austrian President. The Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) had many electoral successes under the leadership of Jörg Haider (1986–2000). Haider was the prototype of the far-right populist and demagogue. The likes of Nigel Farage often appear to be Haider-imitators. In 1999, the FPÖ achieved 26.91% in the federal election and became the junior partner in a coalition government with the Conservative Party ÖVP. It was the first time that a far-right party entered a European government since the end of the Second World War. The outcome was Austria’s isolation in the European Union.

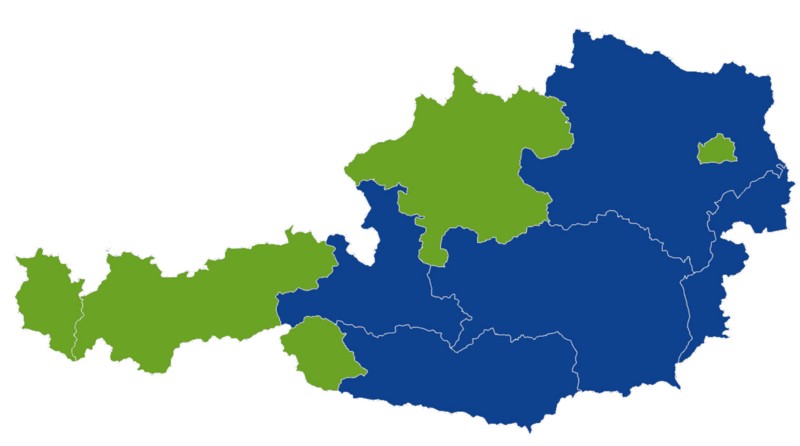

In 2016, Austria again made international headlines: In the Presidential Election’s first round, the FPÖ’s candidate Norbert Hofer achieved the largest share of the votes (35.05%). Many observers expected that Austria would soon have a far-right President and feared he could favour authoritarian and xenophobic politics. The run-off saw Hofer competing against the Green Party candidate Alexander Van der Bellen. Achieving 50.35% of the ballots cast, Van der Bellen won by 30,863 votes. The FPÖ filed a complaint to the Constitutional Court of Austria that ruled in July 2016 that the run-off election had to be repeated because in a number of districts the postal votes were opened or counted earlier than election legislation allowed. The election rerun was planned for October 2nd. It had to be postponed to December 4th because envelopes used in postal voting had manufacturing faults. It therefore remains an open question whether a far-right or a left-wing politician will become Austria’s next President.

We live in times, where politics to a certain extent takes place online and on social media. Every political campaign today makes use of at least Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. In the new study “Racism, Nationalism and Right-Wing Extremism Online: The Austrian Presidential Election 2016 on Facebook” that was published in the journal Momentum Quarterly, I analysed how voters of FPÖ Presidential candidate Norbert Hofer expressed their support on Facebook. They predominantly make use of the Facebook pages of Hofer and FPÖ party leader Heinz Christian Strache. Hofer’s page had in September 2016 around 275,000 “Likes”, Strache’s around 400,000. For Austrian politics, these are very high numbers. Far-right populists and their supporters take to social media in order to communicate ideology online.

We live in times, where politics to a certain extent takes place online and on social media. Every political campaign today makes use of at least Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. In the new study “Racism, Nationalism and Right-Wing Extremism Online: The Austrian Presidential Election 2016 on Facebook” that was published in the journal Momentum Quarterly, I analysed how voters of FPÖ Presidential candidate Norbert Hofer expressed their support on Facebook. They predominantly make use of the Facebook pages of Hofer and FPÖ party leader Heinz Christian Strache. Hofer’s page had in September 2016 around 275,000 “Likes”, Strache’s around 400,000. For Austrian politics, these are very high numbers. Far-right populists and their supporters take to social media in order to communicate ideology online.

The study shows how nationalism 2.0 works. Charismatic leadership is an important element. Supporters commonly expressed an emotional relation to Hofer and called him their “President of Hearts”. Nationalism works with both positive self-presentation of an in-group symbolized by a leadership figure and negative presentations of enemy groups. On social media, Hofer-supporters turned against immigrants and Van der Bellen. Xenophobia was commonly expressed. Users for example argued that immigrants and refugees “do not have our roots, not our religion” or posted: “Please do something before Islam swamps us”, “[There is] mass immigration of criminals…. Rapists, killers etc… Where will this end?”.

In respect to postings about Alexander Van der Bellen, online militancy and calls for violence were not single exceptions. Some examples: “The Austrian Stalin”, “This train station vagabond should go and shit himself”, “Those who voted for van der Bellen ought to be burnt on the stake”, “My weapon is unpacked!”, “And then people wonder if the cold lust to kill comes up in a decent Hofer-voter…”.

Jürgen Habermas argues in his Theory of Communicative Action that political communication in a public sphere requires that citizens respect certain validity claims. The lack of direct embodied, physical and emotional encounter in Internet communication makes it harder to achieve the Habermasian validity claims of truthfulness (communicators lay open their intentions) and normative rightness (communicators respect common moral rules of interaction). As a consequence, online communication tends to be more expressive and affective than offline communication. The inhibition to resort to swearing tends to be lower. Coupled with a political context such as the one of the Austrian Presidential Election, where we find a strong schism of the population between the left and the right, a manifestation of this polarity as online hate speech becomes more likely.

But nationalism 2.0 and right-wing extremism online are not moral or linguistic problems. They have complex social and political causes. In Austria, there are a number of influencing factors, including incomplete Denazification, the long history of Austrian nationalism, the rise of neoliberal capitalism and the associated fall of Social Democracy, far-right xenophobic media, the high level of press concentration, the low level of general education, and the patronage system.

There are no easy fixes to far-right populism, online hate speech and nationalism 2.0. One should in this context Theodor W. Adorno’s words: “The past will have been worked through only when the causes of what happened then have been eliminated. Only because the causes continue to exist does the captivating spell of the past remain to this day unbroken”.

Image sources:

By Grtek [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

By Hermann A.M. Mucke (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons