Trial finds predictive model helps fact-checkers identify false claims with potential to cause harm

- “The basis for developing a rigorous system that can be used by fact-checking organizations, researchers, platforms and others to identify false information that is potentially harmful to individuals or society.”

- “The process can help focus limited resources on the most urgent claims… (and) generates both case studies and aggregate data that underscore the value and impact of work done by fact-checking organizations”

– Study by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers of UoW-led trial

A six-month trial has found that use of a predictive model developed by University of Westminster visiting researcher Peter Cunliffe-Jones helps fact-checkers, and others, to focus on addressing false information with the greatest potential to harm individuals or society.

In the trial, run in 2024, Cunliffe-Jones and three leading fact-checking organisations in Europe and Africa developed tools to forecast the potential consequences of false or misleading claims. The tools use a model set out in his new book, “Fake News – What’s the Harm?” due to be published by University of Westminster Press in June 2025

Cunliffe-Jones, a former news journalist, founded Africa Check, Africa’s first fact-checking organisation, at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2012. He was a board member of the International Fact-Checking Network from 2015 to 2024. He joined the University of Westminster as a visiting researcher in 2019 and published a two-volume work on public policy responses to misinformation in Africa in 2021.

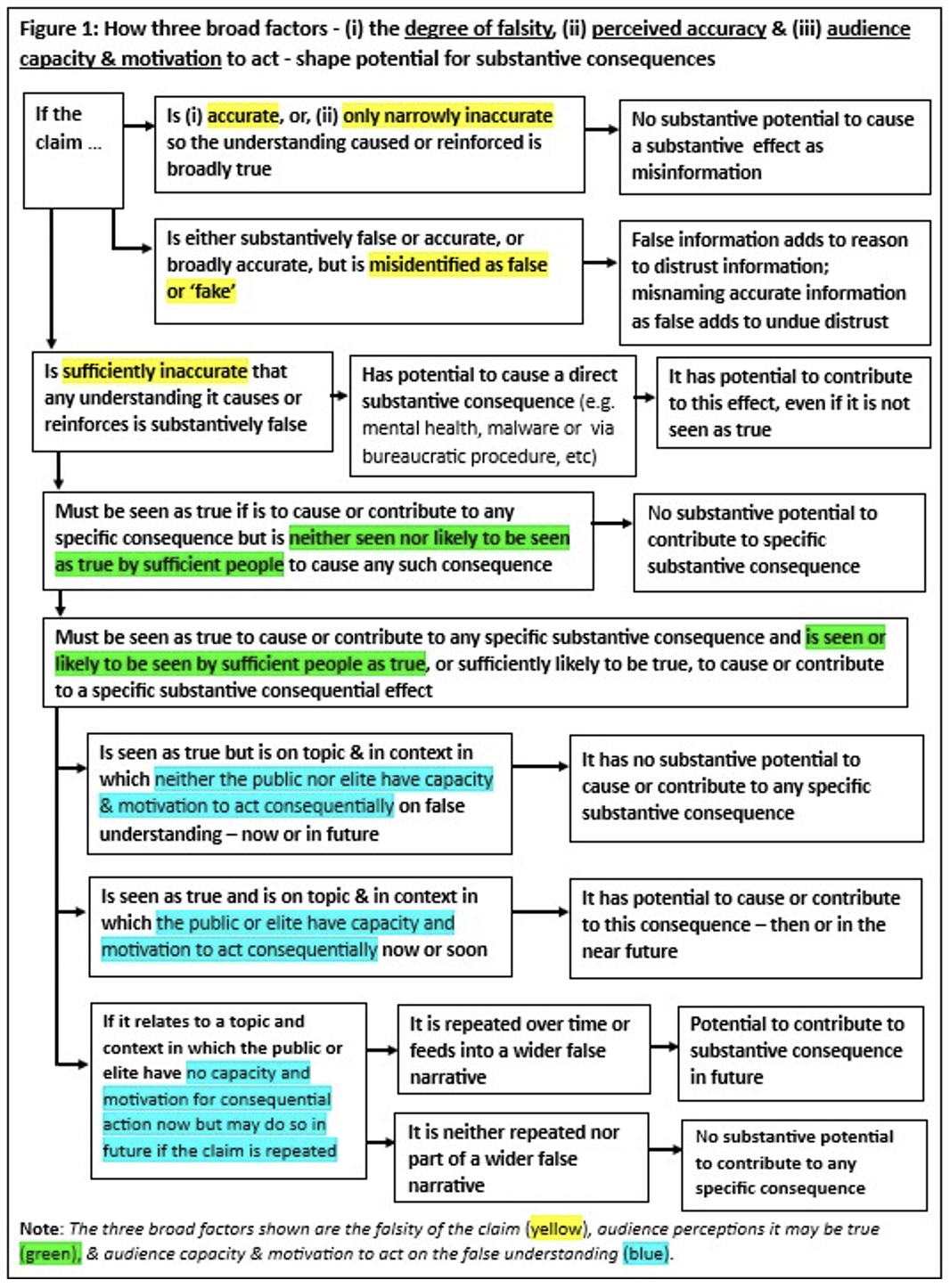

In his new book, based on a four-year review of existing literature and close examination of 250 examples of false information circulating in Africa at the time, Cunliffe-Jones sets out a model for distinguishing between false information that has limited potential to cause effects beyond a false understanding and false information that has a substantive potential to cause or contribute to specific substantive consequences.

- the claim, if believed, causes a substantively false factual understanding

- if so, whether the claim is seen as true by sufficient people to cause the type or types of consequence that could be caused if they act on that understanding

- if so, whether those who see the claim as true have the capacity and motivation to act on this false understanding, now or in future, if the claim is repeated.

As outlined in Figure 1, below, if the claim is either “accurate or only narrowly inaccurate,” and shown in context, it causes no misinformation effect. If the claim is substantively false, the model requires users to take account of both the number who believe the claim, and the number who must act on it to cause a particular consequence. Some effects, such as the consequences of taking a false medication, or engaging in vigilante violence, can occur with action by just one individual. In contrast, a business boycott or flipped electoral outcome may require action by thousands, or more. And if sufficient people do believe a claim, the model asks users to consider their capacity and motivation to act in ways that would cause the consequence concerned.

Figure 1. Peter Cunliffe-Jones, 2025

Reviewing the book that sets out the concept, Professor Lucas Graves of the University of Wisconsin-Madison identified the approach as “a powerful new framework for thinking about the real-world harms that can result from viral misinformation.” Professor Masato Kajimoto of the University of Hong Kong described it as “a nuanced systematic model to identify the claims that pose risks of real-world harm and risks” useful for “professionals and researchers alike.” Professor Andreas Vlachos of the University of Cambridge identified the model as “a very useful guideline to focus fact-checking efforts on claims which matter most”.

Using this model, Cunliffe-Jones and researchers Cayley Clifford, of Africa Check, Estelle Péard, of AFP FactCheck, and Joseph O’Leary, of Full Fact, developed two tools for fact-checkers, researchers and others to use.

The first tool, used at the initial stage of fact-checking when the team select claims to be checked, consists of seven questions to determine whether the claim may have potential, if substantively false, to cause a specific consequence, or harm. Recognising that before the fact-check is completed, the team have limited information, the findings are provisional. The tool also recognizes that there are many reasons, beyond potential harm, to verify claims from using inconsequential but viral claims to teach misinformation literacy to fostering trust in information that is accurate.

According to an independent study of the trial, conducted by doctoral researchers Elohim Monard Rivas and Naomi Mine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, use of this tool by factcheckers “encouraged users to think more critically before pursuing claims, helped them identify harmful scenarios that were not initially evident and refined their decision-making processes … allowing them to focus on more consequential claims while quickly filtering out claims with low potential for real-world harm.”

The second tool, used after the fact-check has been completed, consists of 14 questions to give a clearer answer to the question: whether the claim has a substantive potential to cause a specific substantive consequence or harm. What this tool does, according to the Wisconsin-Madison study, is to generate both granular and aggregate data, and a “library of case studies” of misinformation with potential for serious harm. Where false claims can be shown to have only limited or inconsequential effects, the data can also be used by media freedom advocates to push back against over-regulation of speech.

- The data the model produces and what this means

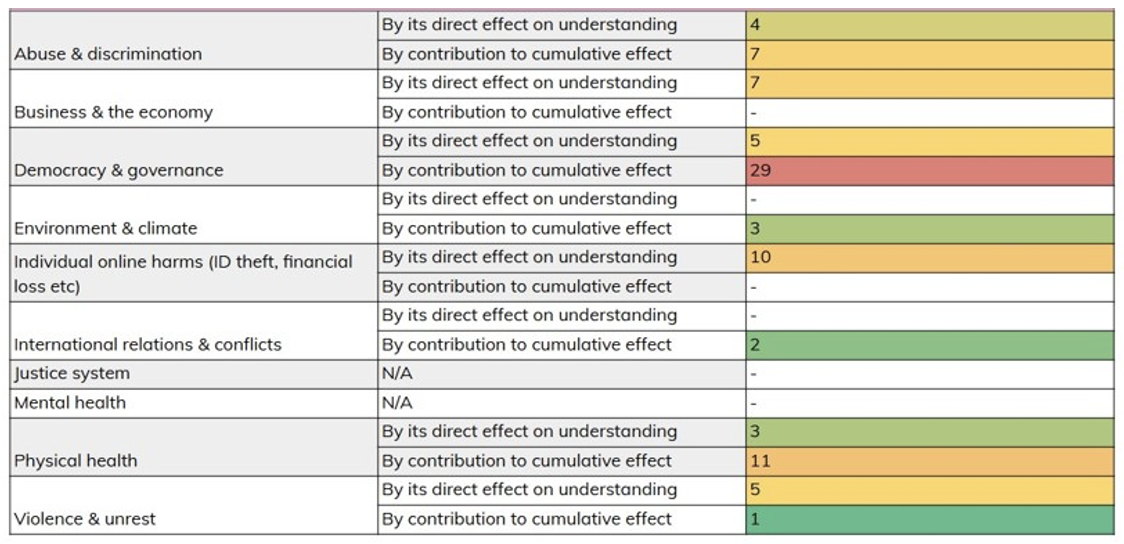

Using the second tool, the trial participants generated a swathe of data helpful in understanding the potential role played by false information in causing or contributing to consequences in eight different fields[1] from business and the economy to physical health. Reviewing the 100 false claims examined in the trial last year, for example, the findings showed potential for consequences occurring in these fields either as a direct effect of action based on the specific false understanding caused, or through the incremental contribution a false claim makes, if repeated sufficiently, to a change in attitude or understanding, over time, that can in time give rise to specific substantive consequences.

Does the claim has a substantive potential to cause a specific substantive consequence or harm? Peter Cunliffe-Jones, 2025

The trial showed that using the tools creates data that also, for example, identifies

- The specific sub-field and mechanism by which the potential consequences may occur g. not simply “effects on health” but “reduced take-up of effective medication due to false information affecting public understanding”, or “a change in public health policy due to effects on the understanding of policymakers”.

- Who this might affect, where and howg. not simply “the public” but “members of a specific community” or “individuals living with a specific health condition”

- Whether specific claims or versions of those claims, that might contribute to cumulative effects, are being repeated thus increasing the potential for such effects

- The source of the claim,g. a social media user, journalist, politician, or institution, and its channel of distribution e.g. social or broadcast media, in a public, business or parliamentary setting.

Participants in the trial also noted that use of the tool can generate real-world case studies, which can be valuable educational resources for audiences, the study of the trial reported. And in France and the United Kingdom, authorities are investigating the consequences of two of the claims found in the trial to have had substantive potential for specific effects.

Fact-checking false claims. Peter Cunliffe-Jones, 2025

The judgements required in predicting potential effects are nuanced and, the study noted: “applying the complex model accurately and consistently across individuals or organizations poses a challenge”. Key to doing so in future will be operational changes to the tools developed for the trial, and an enhanced training program for organizations applying it.”

“Maintaining a comprehensive record of claims run through the model, including those deemed not potentially harmful, will generate a valuable dataset for investigating external validity,” the study added. To fully integrate these tools into daily workflows successfully will require initial training, support, and independent review of the data produced.

“Fake News – What’s the Harm? Four ideas for fact-checkers, policymakers & platforms on countering the consequences of false information & defending free speech” will be published by University of Westminster Press in June 2025

FOOTNOTES

[1] The fields in which the consequences occurred reflect the geography and context of the trial; taking place in Africa and Europe in a period when election campaigns were active. A sample in a different geography and context would be expected to show a different set of potential consequences.