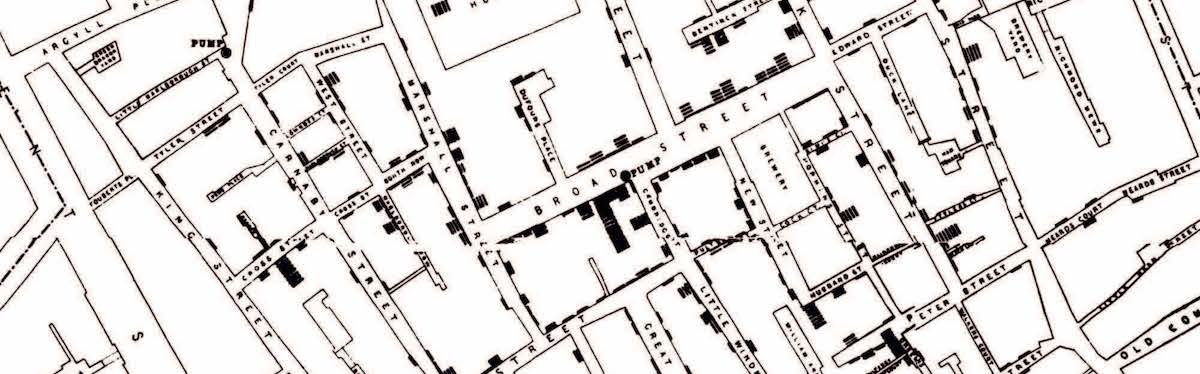

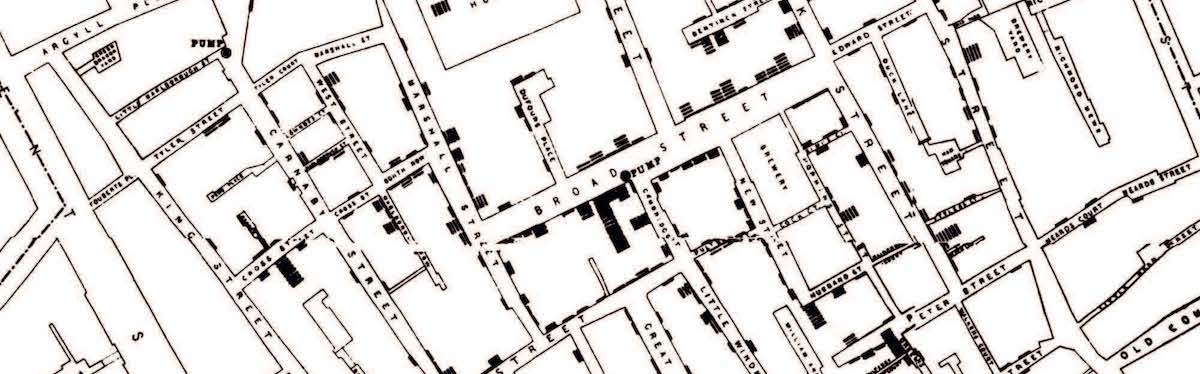

It is perhaps one of the most evocative stories in the field of geography, John Snow, map in hand, storming into Broad Street, tearing off the handle of the water pump and saving countless lives from the misery of Cholera. Snow’s study of the ‘‘Broad Street outbreak’’ has long been heralded as the start of spatioanylitical research and is oft cited as a fundamental example of epidemiology. The story has been handed down, repeated, discussed and presented thousands of times as a vindication of the good things that maps and data can do. But what if the story is wrong, what if our geographic solipsism and romantisatation have distorted our understanding of the methods employed in its creation, and the conclusions that where drawn at the time. Two misconceptions persist around Snow’s maps that have significant implications for how we merge examine geographic information and data at large. Firstly, that it was maps that led Snow to reach the conclusion that Cholera was water born. And Secondly, that his maps provided good evidence for this conclusion.

The first edition of On the mode of communication of cholera (OMCC), published in 1849 had actually contained no maps at all, and nor did Snow allude to the idea that a map had been instrumental in his discovery[i]. It was not until the 1854 edition of OMCC that Snow’s spot map was first published. It would appear then that Snow had developed and tested his hypothesis well before he drew his map. This is not an unlikely scenario given that he was already engaged in an ambitious study of cholera in South London. It was likely these earlier studies that led him to conclude that a sharp localised outbreak pointed to a contaminated pump rather than, as commonly reported, an induction arrived at primarily from the geographical facts of the case. Snow’s map then did not give rise to the insight, but was the tool used to confirm and illustrate an already held hypothesis and conclusion. Furthermore, the idea of using a map was not uniquely his. Snow had cited the work of T. Shapter in OMCC’s second edition, referring his production of spot maps of Exeter to examine the spread of none other than cholera. And spot maps had previously been used by both contagionists and anticontagionists to advance their stance in Yellow Fever research as early as 1798.

Snows map then was really a data visualization to prove a point he had already concluded. Yet, simply plotting deaths on a map did not lead others to reach the same conclusions, nor the immediate, unquestioning adoption of his theory. “On examining the map given by Dr Snow, it would clearly appear that the centre of the outburst was a spot in Broad-street, close to which is the accused pump; and that cases were scattered all round this nearly in a circle, becoming less numerous as the exterior of the circle is approached. This certainly looks more like the effect of an atmospheric cause than any other” was the conclusion reached by Edmund A Parkes in his review of OMCC. Snow’s map alone was not enough to convince either his contemporaries about his, albeit correct, theory.

.